Step by step approach to Afib with RVR

Written by: Ravneet Kamboj MD, Edited by Akshay “Sunny” Elaghandala MD

What is atrial fibrillation?

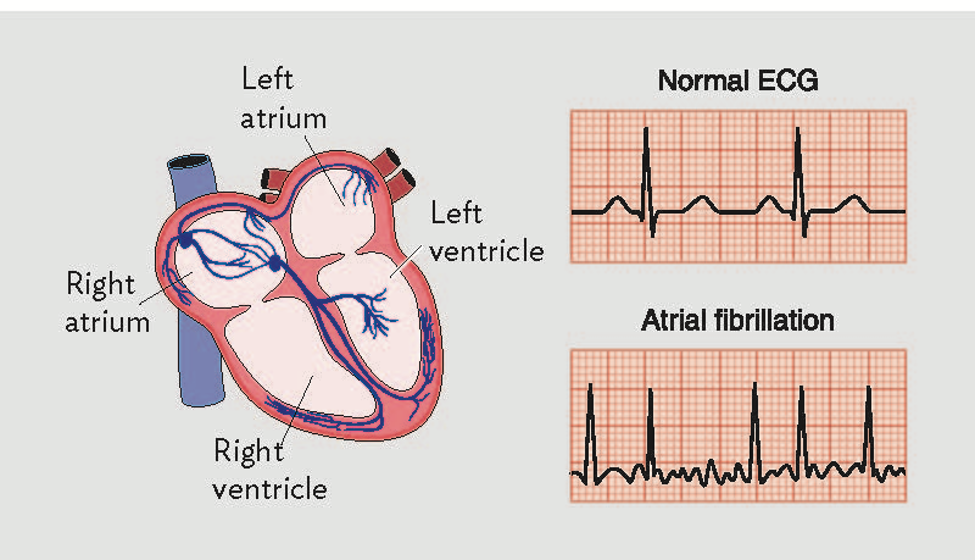

In the healthy heart, normal electrical impulses are generated at the sinoatrial (SA) node and proceed in an orderly fashion to the atrioventricular (AV) node and then down through the bundle of his into the ventricles. This electrical flow produces the characteristic normal sinus EKG.

Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common arrhythmias in the world, is often seen in the Emergency department first and as the population ages, the incidence of afib is expected to rise further. It currently affects an estimated 2.7 to 6.1 million people in the United States and that number is expected to rise up to 12.1 million by 2050 [1]. Atrial fibrillation leads to increased mortality in patients with heart failure [2], increased risk of both the numbers, mortality and disability of strokes [3].

The pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation is thought to involve both focal ectopic points in the atria generating electrical impulses as well as reentrant circuits. When a patient has atrial fibrillation these disorganized impulses compete with the normal electrical activity of the heart. As some impulses pass through the AV node there is a ventricular contraction. It is thought that atrial fibrillation begins paroxysmally which gradually remodels the tissue of the atria leading to more persistent atrial fibrillation [4]. These erratic atrial impulses and irregular conduction through the AV node produce the classic irregularly irregular EKG associated with atrial fibrillation.

What is Afib with RVR

Atrial fibrillation with RVR is the natural course of atrial fibrillation with a high conduction rate to the ventricles leading to rapid ventricular contraction. It is defined as atrial fibrillation with a ventricular rate over 100bpm. However the RACE II trial showed that more lenient rate control of a HR under 110 was non-inferior to more strict control of HR under 80. So in general when treating afib in the ED aim for an HR of 110 or less [5].

It is important to recognize that patients with afib with RVR can present in a myriad of different ways. They can present looking stable and comfortable, or with shortness of breath, syncope, chest pain, dyspnea and many other symptoms. For the emergency medicine physician it is vital to recognize and treat afib with RVR in the correct clinical context. Our first concern is always the ABC’s. It is important to understand how afib with RVR affects hemodynamics.

In patients who are already sick afib can rapidly lead to hypotension, myocardial ischemia and heart failure in the form of pulmonary edema/cardiogenic shock [6]. In a normal, healthy heart, the “atrial kick” portion of atrial systole can be responsible for up to 40% of end diastolic LV volume. In patients with atrial fibrillation, left atrial pressures are increased which can lead to increased pulmonary venous pressures, pulmonary edema and dyspnea. Decreased ventricular filling during atrial systole and impaired diastolic filling of the ventricles due to a rapid heart rate can quickly decrease the LV end diastolic volume. According to the frank-starling law which shows a direct relationship between LVED volume and stroke volume, this reduction in LVED volume can quickly lead to impaired cardiac output, cardiogenic shock and death [7].

Approach to Afib RVR in the unstable patient

The first question to ask yourself is whether the patient’s afib is primary or a compensatory response to something else. One way to think of afib RVR is that it is the “sinus tachycardia” of people who have chronic atrial fibrillation. Think of other causes like hypovolemia, hemorrhage, sepsis, PE, etc. Rate-controlling a patient who has rapid afib as a compensatory mechanism can quickly lead to the patient decompensating.

The Unstable Patient

Knowing what defines an unstable patient is key to recognizing when electrical cardioversion is necessary. An unstable patient is defined by: altered mental status, hypotension, pulmonary edema or chest pain in conjunction with RVR, in a patient where RVR is not a compensatory mechanism for another physiological process. In this case you want to perform a synchronized cardioversion at 200J. Anterior-Posterior positioning of pads with a biphasic machine has the best chance of success [8]. Even so, in critically ill patients electrical cardioversion is much less successful than patients that are previously healthy. This is thought to be attributable to the systemic inflammation and likelihood that these patients have more premorbid conditions than those that are successfully cardioverted [9]. If you have the time and the patient is still awake you can give a dose of etomidate (0.1mg/kg) for mild sedation prior to cardioversion, as it is still a painful procedure. In unstable patients that have been cardioverted the AHA recommends that heparin should be started due to the risk of thrombus [10] if the afib has been ongoing for over 48 hours or if the duration of afib is unknown.

When cardioversion fails

Given the evidence that electrical cardioversion often fails in critically ill patients, our attention must return to the patients ABC’s. At this point you have determined that your patient is unstable, that the RVR is the primary source of their instability and not a compensatory response, and have attempted cardioversion without success. The next step is to control the patient's blood pressure before trying to control the rate. This is the time to reach for pressors. One useful agent here is phenylephrine. Here is a review of its properties which makes it useful in afib.

Phenylephrine

Pure alpha agonist

Works by increasing systemic vascular resistance

Can cause a reflex bradycardia helping control the heart rate

Does not stimulate beta receptors, avoids stimulating the heart directly

The phenylephrine can be given as a 50-200mcg push q2 minutes or as a drip of 40-180mcg/min titrated to a diastolic pressure of over 60. Since norepinephrine is also primarily an alpha agonist a drip of 0.05-0.1mcg/kg/min can be used as well. But norepinephrine will also increase heart rate and have some inotropic support.

Once the patient's blood pressure has some support it is time to choose a rate control agent. One option is Amiodarone. Some advantages of the medication are that it can be safely given to patients in heart failure, it acts as an antiarrhythmic and may convert the patient to sinus rhythm as well as control the rate [11]. Another advantage of amiodarone in the critically ill patient is that it causes less hypotension than agents like diltiazem [12]. The dosing of amiodarone is a 150mg bolus over 10 minutes and then an infusion rate of 1mg/min. The 150mg bolus can be repeated up to two more times q45 minutes if there is no response.

Magnesium

Another option to consider is magnesium. The mechanism is unclear and perhaps may be due to calcium antagonism and slowing conduction through the AV node [14]. There is some evidence to suggest that when used in conjunction with other antiarrhythmic drugs it may help increase the success of rate control. Given that it has a good risk profile and low chance of causing side effects it may be worth trying if your patient is still unstable at this point and you are having difficulty controlling their rate.

In general be extremely careful using beta blockers and calcium channel blockers in these patients

One option to consider is Esmolol. This is a beta blocker with very “fast on/fast off” properties making it ideal to be able to titrate the patient's rate to exactly where you want it. A small study done in an emergency department showed that esmolol was more effective for rate-control than amiodarone [13]. Be cautious with esmolol as its rapid effect can also cause rapid hypotension if it is not titrated carefully. The dosage of esmolol to use in this situation is to bolus 500mcg/kg over 1 minute and then transition to 50mcg/kg/min drip (up to a max dose of 200mcg/kg/min).

It is also possible to use diltiazem in these patients, however be extremely careful about precipitating hypotension and it is generally advised to avoid it in patients with decompensated heart failure or those who are unstable. Digoxin is another option to consider and has some positive inotropic effects and may be helpful in patients with heart failure, however it's time to onset often makes it less useful in a time sensitive situation such as a crashing patient in the Emergency Department. If all else fails, attempt cardioversion again and look for other compensatory causes for the patient’s atrial fibrillation that you may be missing.

Image from [7] Arrigo et al.

Approach to Afib RVR in the stable patient

Consequences of Afib

A lot of atrial fibrillation even with rapid ventricular rates that an Emergency Physician will see in their career will not be unstable patients. Oftentimes patients will be hemodynamically stable but present for a variety of symptoms such as shortness of breath, palpitations, dizziness, syncope or feelings of anxiety. It is important to understand what the complications of atrial fibrillation are and why as an Emergency Medicine doctor it is essential to know the management of atrial fibrillation in both life threatening situations as described above and in more routine situations. Even when atrial fibrillation does not lead to immediate hemodynamic compromise its long term effects are significant drivers of morbidity and mortality. Atrial fibrillation is responsible for a significant percentage of embolic strokes, and it also increases the risk of heart attack and heart failure [16].

Anticoagulation

Due to the high risk of thromboembolic strokes all patients with atrial fibrillation should be considered for anticoagulation. Patients can be risk stratified using the CHA₂DS₂-VASc score. The choice of anticoagulation agent depends on individual patient factors. These factors include cost and whether a patient has afib associated with a valve. In valvular afib the medication of choice is Warfarin. The AHA guidelines recommend that those with a prior stroke, TIA or CHA₂DS₂-VASc over 2 receive anticoagulation. Those without valvular afib can be treated with DOAC’s such as apixaban and rivaroxaban. The use of these medications should be balanced with the bleeding risk of the patient [18]. The superiority of anticoagulants over dual antiplatelet therapy in reducing thromboembolic events in aifb was proven in the ACTIVE-W trial [19].

Rate vs Rhythm Control

The decision on how to treat a patient with afib will often come down to the timeline of their disease. Atrial fibrillation can be broken down by duration of symptoms. There is new onset afib, paroxysmal, persistent and permanent afib [20].

-Paroxysmal is usually self terminating within 2 days but can last up to one week

-Persistent afib means a patient is in afib for more than a week but less than a year

-Permanent afib means that a patient is always in atrial fibrillation

There is debate over whether rate or rhythm control is superior, and practice patterns vary widely based on both geographic location. In Canada 45-85% of patients are treated with rhythm control whereas in the United States it is approximately 25% [20] The original trial showing no difference in outcomes between the two strategies was the AFFIRM trial [21], since cardioversion both electrical and chemical require more resources, rate control has become the preferred treatment strategy. However more recent studies such as the large multicenter “EAST-AFNET-4” trial suggest that rhythm control and anticoagulation initiated early on in a patient’s disease course may decrease cardiovascular complications vs rate control [22], although not in the acute ED phase.

Rate control

This is the strategy that will most often be employed in the Emergency Department. In a stable patient with Afib the two preferred classes of medications used are beta blocker and calcium channel blockers. First, if a patient is already on one class of medication, it is usually wise to stay with that same class of medications. During atrial fibrillation the atria are sending impulses to the AV node at rates exceeding 250bpm at times. Due to the inherent refractory time of the AV node only some impulses get conducted. These rate control agents work by further slowing conduction through the AV node or increasing the refractory time. Slowing the ventricular rate improves filling and decreased negative cardiac modeling that persistent high rate afib can cause. Using both classes together carries the theoretical risk of causing complete heart block and hemodynamic collapse. Also it is beyond the scope of this article but make sure to exclude afib with preexcitation syndrome before using any AV nodal blocking agents. This is important to know because the combination of AV nodal blocking agents with preexcitation syndromes like Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome can lead to dangerous arrhythmias (AV nodal blockade results in unopposed conduction through the accessory pathways, precipitating lethal arrhythmias).

Beta blockers work by binding beta receptors in cardiac and nodal tissue. Metoprolol is the standard beta blocker used in atrial fibrillation. It is first given as a 2.5-5mg IV push dose. After the first dose assess for effectiveness, the IV push can be repeated every 5 minutes for a total IV dose of 15mg. If the patient responds you may start PO metoprolol about 20 minutes after the last IV push. Standard PO dosing is 25mg-50mg q6h [18]. Consider avoiding beta blockers in patients with Asthma or other forms of reactive airway disease.

Non dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are the CCB’s of choice in atrial fibrillation. The standard medication used is diltiazem. They have less peripheral vasodilation than dihydropyridine CCB’s. They work by causing a direct negative inotropic effect on cardiac tissue as well as slowing conduction through the SA and AV node. However due to this negative inotropic effect extreme caution must be used in patients with heart failure. In patients with poorly compensated heart failure using diltiazem can cause profound hypotension and shock. [18]. In one trial by ‘Fromm et al’., when comparing diltiazem vs metoprolol, diltiazem was 50% more successful at achieving rate control at 30 minutes [23].

The dosing of diltiazem for atrial fibrillation is a 0.25mg/kg bolus with a max dose of 25-30 mg. If a patient responds you can start a diltiazem drip at 5-15mg/hr [18]. At this point the patient can be admitted on the drip dose or started on diltiazem PO. Standard PO dosing is diltiazem 60mg QD

If a patient does not have any other illnesses or associated complications, has a plan for anticoagulation and cardiology followup they can be discharged. However this will vary based on practice location and local culture [24].

Rhythm control in the Emergency department

Table from Frankel et al. [25]

While rhythm control as a strategy is more commonly done in Canada vs the United States there are some times where it may be the preferred strategy.

The Ottawa Aggressive protocol is one way to stratify patients that may be able to be cardioverted. According to the protocol patients can be considered for rhythm control and discharge from the Emergency department if they meet these criteria. In their study they decided to cardiovert patients that had these features [26].

Patient is stable without signs of ischemia, hypotension or acute CHF

Onset time is clear and less than 48 hours, in this case do not need anticoagulation

OR

Patient has already been on anticoagulation for 3 weeks

Patient is clinically stable

The patients were chemically cardioverted with 1G of procainamide over 60 minutes. They found that this successfully converted 58.3% of patients. Of those who did not convert with procainamide electrical cardioversion had a 91.7% success rate. They found that 96.8% of patients were able to be discharged with a relapse percentage of 8.6% at 7 days. Of the 660 patients in the study there were no events of torsades, thromboembolic events or death [26] So while not commonly done here in the United States or not likely to be done with a sick,elderly patient population there may be a role for early rhythm control and discharge of stable patients in the Emergency Department.

Take Home

Atrial fibrillation in the Emergency Department is a broad topic, however we can try to summarize the basic points here. When a patient first comes into the ED, first decide

Stable or Unstable

If the patient is unstable, resuscitate them, determine if their atrial fibrillation is causing their instability as a response to another pathology. If the RVR is the reason for instability proceed to electricity, drugs and pressors as needed. Remember to support the blood pressure as much as possible before trying rate control agents. Be very judicious or completely avoid IVF fluids as the patient may already have or develop pulmonary edema, due to cardiogenic shock from their decreased stroke volume (bedside echo and IVC views can help with this decision). In these patients make sure to balance their blood pressure and any effects from medications you choose to control the afib.

If the patient is stable, decide on the need for an oral anticoagulation agent if they are not already on one. In most cases the go-to option will be to rate control the patient and then disposition them based on their presenting complaint, comorbidities or if they have any other pathologies. If it is a younger patient, with new onset afib, that appears well and does not have many comorbidities, or if they appear more uncomfortable with the afib you may want to consider rhythm control. All in all there is still ongoing debate into the best management of this complex disease and Emergency Medicine physicians are often the first point of contact when patients develop this arrhythmia

References

Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285(18):2370-2375. doi:10.1001/jama.285.18.2370

Maisel WH, Stevenson LW. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(6A):2D-8D. doi:10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03373-8

Wolf PA, Dawber TR, Thomas HE Jr, Kannel WB. Epidemiologic assessment of chronic atrial fibrillation and risk of stroke: the Framingham study. Neurology. 1978;28(10):973-977. doi:10.1212/wnl.28.10.973

Iwasaki YK, Nishida K, Kato T, Nattel S. Atrial fibrillation pathophysiology: implications for management. Circulation. 2011;124(20):2264-2274. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019893

Van Gelder IC, Groenveld HF, Crijns HJ, et al. Lenient versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1363-1373. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1001337

A. Rudiger, V.-P. Harjola, A. Müller et al., “Acute heart failure: clinical presentation, one-year mortality and prognostic factors,” European Journal of Heart Failure, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 662–670, 2005.

Arrigo M, Bettex D, Rudiger A. Management of atrial fibrillation in critically ill patients. Crit Care Res Pract. 2014;2014:840615. doi:10.1155/2014/840615

Kirchhof P, Eckardt L, Loh P, et al. Anterior-posterior versus anterior-lateral electrode positions for external cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9342):1275-1279. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11315-8

Mayr A, Ritsch N, Knotzer H, et al. Effectiveness of direct-current cardioversion for treatment of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, in particular atrial fibrillation, in surgical intensive care patients. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(2):401-405.

January C, Wann S, Joseph S, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. J Am College Cardiol 2014.

Zimetbaum P. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy for atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;125(2):381-389. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019927

Delle Karth G, Geppert A, Neunteufl T, et al. Amiodarone versus diltiazem for rate control in critically ill patients with atrial tachyarrhythmias. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(6):1149-1153. doi:10.1097/00003246-200106000-00011

Milojevic K, Beltramini A, Nagash M, Muret A, Richard O, Lambert Y. Esmolol Compared with Amiodarone in the Treatment of Recent-Onset Atrial Fibrillation (RAF): An Emergency Medicine External Validity Study. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(3):308-318. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.12.010

William L. Baker, Treating arrhythmias with adjunctive magnesium: identifying future research directions, European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy, Volume 3, Issue 2, April 2017, Pages 108–117, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjcvp/pvw028

Davey MJ, Teubner D. A randomized controlled trial of magnesium sulfate, in addition to usual care, for rate control in atrial fibrillation. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45(4):347-353. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.09.013

Morillo CA, Banerjee A, Perel P, Wood D, Jouven X. Atrial fibrillation: the current epidemic. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(3):195-203. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2017.03.011

Nesheiwat Z, Goyal A, Jagtap M. Atrial Fibrillation. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan

January C, Wann S, Joseph S, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: executive summary. J Am College Cardiol 2014

Connolly S, Pogue J, et al. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367(9526):1903-1912. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68845-4

Stiell IG, Clement CM, Brison RJ, et al. Variation in management of recent-onset atrial fibrillation and flutter among academic hospital emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(1):13-21.

Saksena S, Slee A, Waldo AL, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in the AFFIRM Trial (Atrial Fibrillation Follow-Up Investigation of Rhythm Management). An assessment of individual antiarrhythmic drug therapies compared with rate control with propensity score-matched analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(19):1975-1985. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.03

Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, et al. Early Rhythm-Control Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1305-1316.

Fromm C, Suau SJ, Cohen V, et al. Diltiazem vs. metoprolol in the management of atrial fibrillation or flutter with rapid ventricular rate in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 2015;49:175-182.

Wakai A, O’Neill JO. Emergency management of atrial fibrillation. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(932):313-319. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.932.313.

Frankel G, Kamrul R, Kosar L, Jensen B. Rate versus rhythm control in atrial fibrillation. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(2):161-168.

Stiell I. et al.. "Association of the Ottawa Aggressive Protocol with rapid discharge of emergency department patients with recent-onset atrial fibrillation or flutter". CJEM. May 2010. =12(3):181-91.

![Image from [7] Arrigo et al.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bc94f5b9b7d1515843688af/1608347613775-P0N0REN44NCE8RFUP093/Picture1.png)

![Table from Frankel et al. [25]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bc94f5b9b7d1515843688af/1608347761500-74O52EZDZ88Q4YAMNTDG/Picture1.png)