Unstable Cervical Spine Fractures

Written By: Justin Song, DO PGY-1; Edited by: Timothy Khowong, MD, MSEd

Background

All trauma patients should be evaluated for unstable cervical spine injury. This is because studies show that up to approximately 5-10% of patients who experience blunt trauma have cervical spine injuries and missing these can lead to disastrous consequences. A high index of suspicion is warranted especially in patients presenting after a high-energy mechanism of injury and in those who are intoxicated or unconscious even if there are no clear signs of trauma. The cervical spine can be cleared after a thorough physical examination and/or CT imaging to rule out stable vs unstable c-spine fractures. There are two clinical decision tools that we can use to determine the need for radiographic imaging: Canadian C-spine Rule (CCR) and NEXUS criteria. These tools can be especially helpful in reducing unnecessary imaging in trauma patients that have a low risk for c-spine injury.

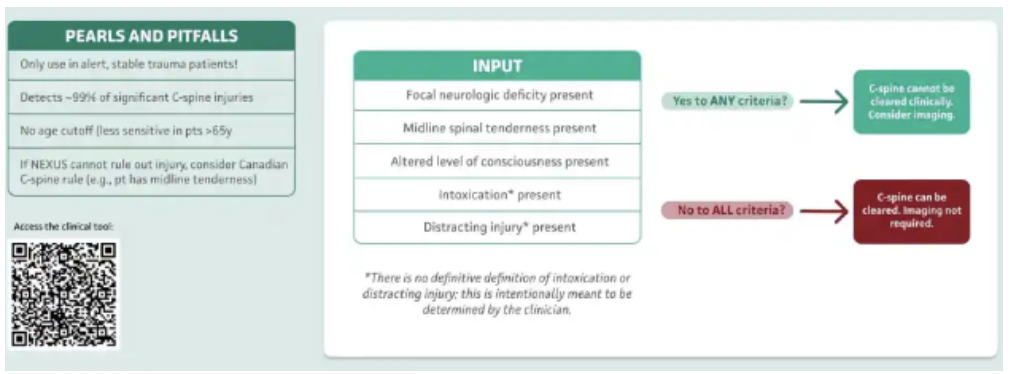

NEXUS criteria allows us to safely clear a patient’s c-spine without imaging only if they meet ALL of the following requirements.

No midline tenderness

No distracting injury

No neurologic deficit

No intoxication

No altered mental status

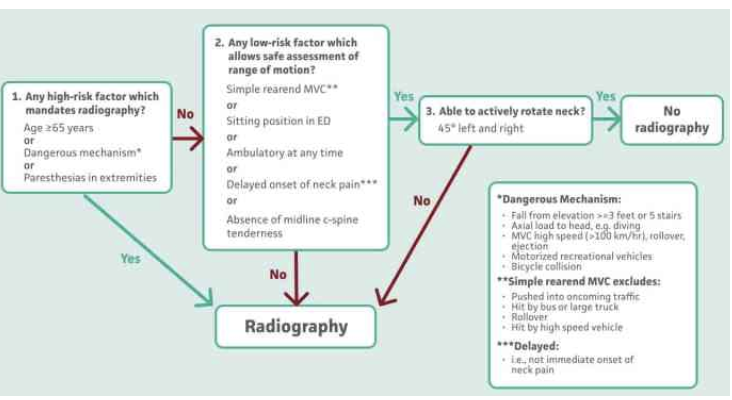

CCR uses 3 categories as shown below to assess if a patient requires imaging. The limitation is that CCR can only be applied to patients who are <65, GCS 15, and in stable condition following a trauma.

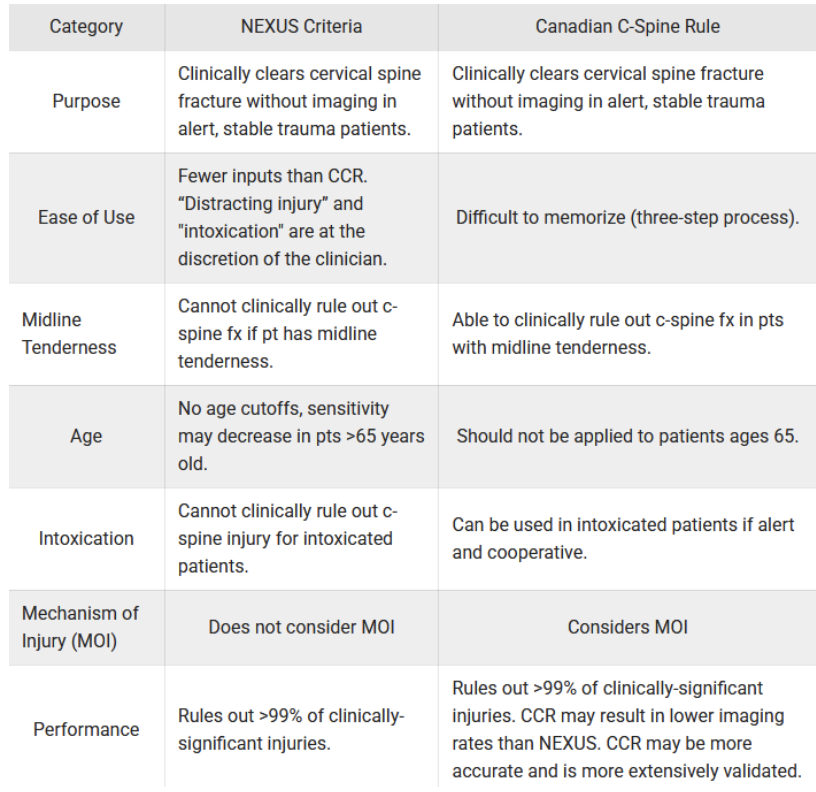

Both NEXUS and CCR can help physicians rule out c-spine fractures. NEXUS is simpler, but CCR is more well validated and can be applied to patients with midline tenderness. They each have their pros and cons that need to be taken into consideration when using them. A summary of the differences between the two can be seen in the table below:

Once you determine if a patient needs a CT imaging of their neck and obtain the scans, make sure to get into the habit of reading them on your own. While reading CT scans of the c-spine can appear overwhelming, this process can be easily done if you follow these simple “ABC’S”:

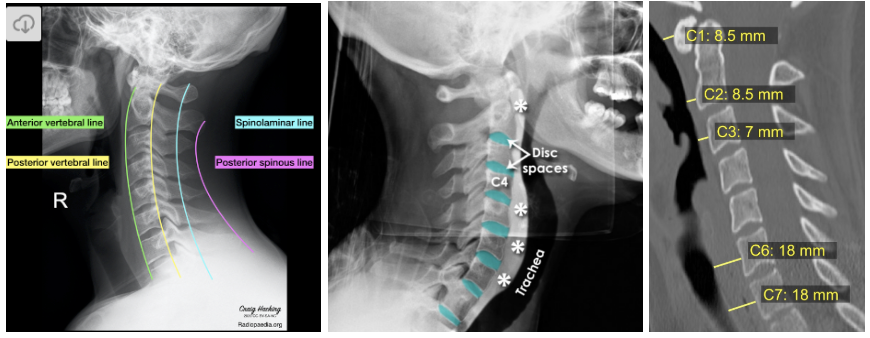

A - Alignment - trace along the anterior vertebral line (anterior longitudinal ligament), posterior vertebral line (posterior longitudinal ligament), spinolaminar line (ligamentum flavum), and tip of the spinous processes to see of for any disruptions

B - Bones - assess the bones in the axial/sagittal/coronal views for any fractures

C - Cartilage - evaluate for any narrowing or asymmetry between the vertebral bodies and spinous processes

S - Soft tissue - examine the prevertebral soft tissue (narrower 5-10mm from C1-C4 and thickens starting C5 due to esophagus lying anteriorly) since soft tissue swelling my point towards a fracture

J - Jefferson’s fracture (C1 burst fracture)

High-energy trauma with axial vertical compression force (ie. head trauma after diving into shallow end) resulting in fracture of the anterior and posterior arches of C1 vertebrae

Low incidence of spinal cord injury due to: spinal canal being the widest at C1 and the burst fx tends to further widen the spinal canal. Also, spinal cord injuries at this level are typically fatal and patients do not survive to receive medical attention

Often associated with other cervical fractures (most commonly the dens, C2 posterior arch or vertebral body), vertebral artery injury, and disruption to the transverse ligaments

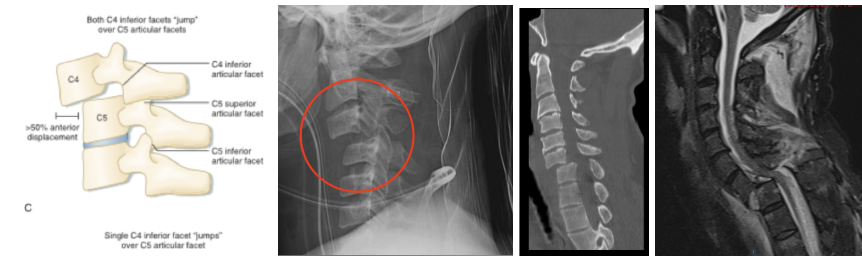

B - Bilateral facet dislocation

Caused by extreme neck flexion and anterior subluxation resulting in damage to the annular fibrosis and anterior/posterior longitudinal ligaments

Disruption to these complexes result in significant anterior displacement of the superior vertebral body by ≥50% compared to the inferior vertebral body

Complications involve injury to the spinal cord and vertebral arteries

O - Odontoid (dens) fracture

Fracture of the dens at C2 typically caused by flexion loading, but can also occur from extension loading.

Classified into 3 types depending on the level of injury

Type 1 = avulsion fracture of the dens, stable and rare

Type 2 = fracture at base of dens, unstable, most common, prone to nonunion, frequently associated with neurological deficits

Type 3 = dens fracture involving vertebral body, unstable, neurological injury if fragments are displaced

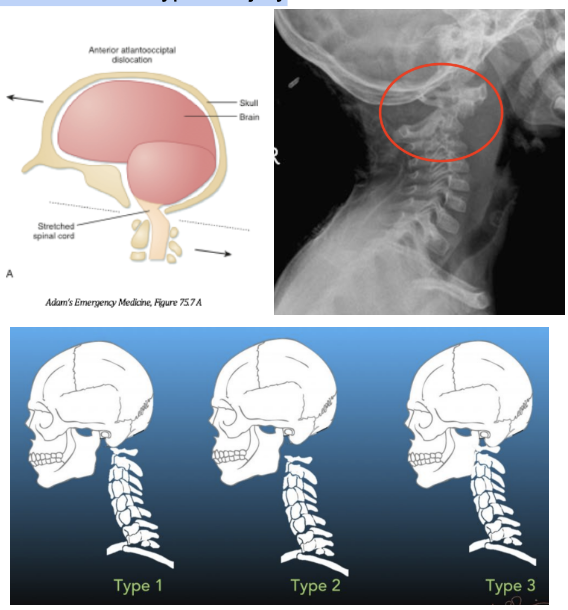

A - Atlanto-occipital dislocation (AOD)

Highly unstable injury that is also called “internal decapitation” as it results in complete dissociation of C1 from the occiput due to rupture of the transverse ligaments stabilizing the atlanto-occipital joint

Different presentations, but the most common is anterior dislocation (type 1), but can also occur superiorly (type 2), and posteriorly (type 3)

Highly fatal injury due to stretching of the brainstem causing respiratory arrest and death

More common in pediatric patients due to immature atlanto-occipital joint and certain high-risk populations (ie. Down’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis) due to increased laxity at the AO joint

This injury can easily be missed on imaging since the joints may reapproximate between the time of the incident and imaging. Physical exam findings like mandibular fx, chin lacerations, and injury to the posterior pharyngeal wall can clue you into the this type of injury

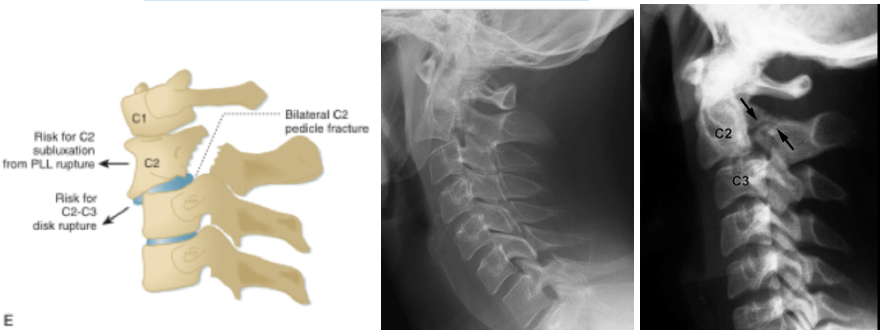

H - Hangman’s fracture (C2 pedicular fracture)

Forceful hyperextension of the head with neck distraction resulting in bilateral C2 pedicular fracture with/without anterior translation of C2 on C3

Also known as traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis, but the term “hangman’s fracture” is misleading since this injury is more likely to result from MVC or fall

Three types classified by degree of translation and angulation, but Type 1 is stable and Type 2 and 3 are unstable

Often not an isolated fracture and up to 30% of patients have an additional cervical spine injury to contiguous or noncontiguous levels

Spinal cord injuries are rare since the diameter of the spinal canal is the largest at C2 and the subluxation widens it further

T - (Flexion) Teardrop fracture

Most severe injury to the cervical spine caused by hyperflexion of the neck with additional compressive forces (ie. shallow water diving injury, MVC deceleration)

Most commonly occurs at C5-C6 and results in a triangular (‘tear-drop’ shaped) avulsion fracture at the anterior column and posterior displacement of the vertebral body causing disruption to the PLL and facets

Highly unstable and associated with spinal cord injuries in up to 50% of cases such as anterior cord syndrome

Treatment and Disposition:

Once an unstable cervical fracture is diagnosed, care must be maintained to prevent further injury. A cervical collar should be maintained and spine surgery should be consulted for further guidance in management. If neurogenic shock occurs due to loss of sympathetic tone, vasopressors should be initiated. High cervical spine fractures may lead to respiratory failure, in which cases, the patient may need to be intubated. The majority of these patients should be admitted to the hospital.

Summary

Missed cervical spine fractures can have devastating effects, so you should have some index of suspicion for c-spine injury in every trauma patient that presents to the ED. A thorough history and physical examination is important to help clear the cervical spine and you can additionally use the NEXUS criteria or Canadian C-spine Rule to help guide your clinical decisions to image the patient. Learn how to read your own CT scans as you try to differentiate between c-spine injuries from the stable and unstable types.

References

Bhatti, M. (2022, September 22). Unstable C-Spine fractures. https://sinaiem.org/foam/unstable-c-spine-fractures/

Blog, N. (2019, April 23). Unstable cervical spine fractures — NUEM blog. NUEM Blog. https://www.nuemblog.com/blog/cervical-spine-fractures

Chapter 11. Pathologic Conditions of the spine. (n.d.). McGraw Hill Medical. https://accessemergencymedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?sectionid=42496373&bookid=573#57256253\

Coneybeare, D. (n.d.). C-Spine injuries + CT interpretation. Core EM. https://coreem.net/core/c-spine-injuries/

Forsthoefel, C., MD. (n.d.). Cervical facet dislocations & fractures - spine - orthobullets. https://www.orthobullets.com/spine/2064/cervical-facet-dislocations-and-fractures

Propersi, M. (2025, June 16). MDCALC Wars: NEXUS Criteria vs Canadian C-Spine Rules. REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog. https://rebelem.com/mdcalc-wars-nexus-criteria-vs-candian-c-spine-rules/