Nonaccidental Trauma Patterns

Written By: Michelle Qu, DO PGY-1; Edited by: Timothy Khowong, MD, MSEd

Background

Nonaccidental trauma (NAT) is the leading cause of childhood traumatic injury and death in the United States. Patients of many different ages enter our emergency rooms, including children. Children of abuse will often present to the hospital with many different complaints, and it is up to the Provider to have a low threshold to intervene. As mandated reporters, it is important to recognize the indicators of abuse. In this blog post, we will focus more on the orthopedic findings that can guide a clinician in suspecting NAT.

If you ever have a high suspicion, please separate the child from the parents, get Child Protective Services involved as soon as possible and then get a skeletal survey as part of their clinical work up.

Red Flags

It’s important to recognize red flags from the encounter itself. Some of which include but are not limited to:

Injury in a nonambulatory/totally dependent child (i.e., child that has not begun to walk yet due to age, child with developmental delay)

Injury that is inconsistent with the history that is being told (i.e., long bone fracture after a simple trip and fall)

In the setting of a trip and fall, falls are common but those that result in fractures are rare (even more rare in stronger bones such as the long bones of the body)

There is a delay in time in which the caretaker seeks medical attention for the child

Multiple fractures in different places of the body without an underlying genetic diagnosis that is explanatory for bone fragility

Torn frenulum (specifically in young, nonambulatory children as they can’t generate enough force to tear the mucosa)

This can occur in settings where there is forceful feeding with a bottle, utensils or even a direct blow to the mouth

Fractures Highly Concerning for NAT

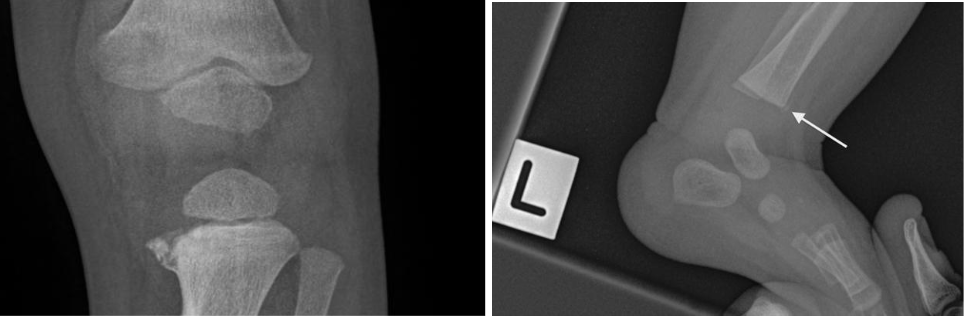

Metaphyseal Fractures

These are also known as bucket handle/corner fractures. These are the most SPECIFIC and PATHOGNOMONIC for nonaccidental trauma. This type of injury often occurs as microfractures from whiplash/shearing forces. This often presents exclusively in children under 2 years old because they are small enough to be shaken and not enough muscle development has occurred to protect their own limbs. However, please check patient’s birth history! In newborns, this can be a finding that can occur after traumatic deliveries where the baby presents in the breech position.

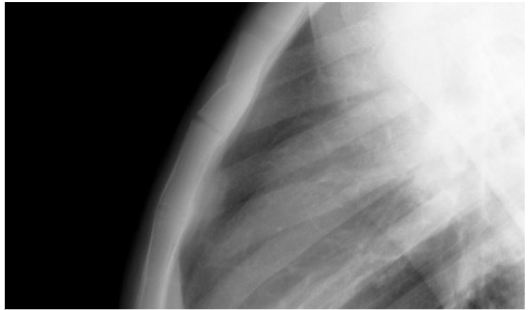

Rib Fractures

Posterior rib fractures are especially specific for nonaccidental trauma and may not have any overlying skin changes such as ecchymosis. They may result from a child’s torso being squeezed inappropriately by a caregiver.

Skull Fractures

Skull fractures in the non-parietal bone are considered specific for nonaccidental trauma. Parietal bone fractures are more suggestive of accidental trauma. Other findings that involve the skull that are suspicious include:

Fractures that involve multiple bones of the skull

Fractures that cross suture lines

Depressed fractures, also known as Fracture a la Signature

Scapular Fractures

These fractures are normally found after high energy trauma, where 50% scapular fractures are due to motor vehicle accidents.

Sternal Fractures

Outer Third Clavicle Fractures

Fractures Moderately Suspicious for NAT

Spiral Humeral fracture

Spiral fractures often occur from a twisting mechanism, while transverse fractures to the humerus typically occur with direct blow to the arm.

Separation of epiphysis

Some other fractures to look out for that are considered moderately specific for nonaccidental trauma are:

Fractures that are differing in ages involving bilateral limbs

Digital fractures in non-ambulating children

Vertebral fractures, vertebral subluxations.

Management and Disposition of a Patient with Suspected NAT

If you suspect NAT, it is important to ensure the continued safety of the child. As mandated reporters, an ACS referral needs to be placed by you or a member of your team. Management of traumatic injuries depends specifically on the type of injury and can range from immobilization to orthopedic and/or trauma surgery evaluation. Disposition must be determined based on the best interest of the patient. If they are stable for outpatient management of injuries, they must be discharged to a safe place, whether that be the care of a different family member or into the custody of CPS. Some patients will require admission for their injuries or to get more time for a safe disposition to be arranged.

References

Campos A, Deng F, Alhusseiny K, et al. Suspected physical abuse. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 04 Feb 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-10133

Heyming T, Knudsen-Robbins C, Sharma S, Thackeray J, Schomberg J, Lara B, Wickens M, Wong D. Child physical abuse screening in a pediatric ED; Does TRAIN(ing) Help? BMC Pediatr. 2023 Mar 10;23(1):117. doi: 10.1186/s12887-023-03927-0. PMID: 36894913; PMCID: PMC9998251.

“Pediatric Sternum Fracture: Pediatric Radiology Reference Article: Pediatric Imaging: @pedsimaging.” Pediatric Imaging, 18 Oct. 2024, pediatricimaging.org/diseases/sternum-fracture/.

Troxler, D.; Mayr, J. POCUS Diagnosis of Sternal Fractures in Children without Direct Trauma—A Case Series. Children 2022, 9, 1691. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9111691

McRae R, Max Esser M, Practical Fracture Treatment Fifth Edition, Churchill Livingstone, 2008