Push Dose Pressors: Your Quick & Dirty Guide

Written by Dr. Nathalie Briones, Edited by Dr. Richard Shin

Okay so I’ll admit it. I love me some push-dose pressors.

In the resuscitation bay, there are a handful life-saving tools we regularly keep within an arm’s reach during each resuscitation – tools for some of those critical moments that could prevent your crashing patient from coding if you quickly employ them when needed. Some of my all-time favorites are obviously the ultrasound machine, Bi-Pap, the Glidescope, etc., etc...… But another favorite of mine is a tool that works within seconds and is a great temporizing measure in patients with dangerously low perfusion when you need an immediate increase in blood pressure, STAT.

Enter: Push-dose pressors.

I don’t think a lot of ED providers tend to consider push-dose pressors as a tool to keep in their back pockets during some of these split-second moments that they’re needed, but I also think not many providers may be familiar enough with them to be comfortable mixing & administering them during these high-stress situations. Anesthesiologists have been using bolus-doses of vasopressors for decades in the OR, but the concept has only recently penetrated into the ED/ICU resuscitation world the past few years, with very little EM-based literature published on the subject.

Nevertheless, having a solid understanding of when & how to give push-dose vasopressors can be a vital (and practical) tidbit of ED resuscitation knowledge that can save your critically hypotensive patients from hemodynamic collapse if you have it in your arsenal.

What are push-dose pressors?

Push-dose pressors are simply small intravenous bolus doses (“pushes”) of vasopressors & inotropes that can serve as a great temporizing measure in patients who are severely hypotensive, in order to rapidly increase cardiac and brain perfusion while other measures are being initiated.

Push-doses of these pressors are useful in a number of given situations, including:

An anticipated transient drop in blood pressure (e.g. peri-intubation)

As a bridge prior to the initiation of a vasopressor drip (while the drip is being mixed, a central line is being placed, etc.)

Temporizing perfusion of critical organs (heart, brain, kidneys) while aggressive fluid and blood product replacement is taking time to effect

To keep in your pocket “just in case” during transport of critical patients (e.g. to and from the ED or ICU)

Prehospital EMS administration (which has been on the rise recently)

The most utilized agents for push-dose pressors in the emergency department are currently phenylephrine as well as epinephrine, which both have rapid onset and short-lived effects. Other agents, such as ephedrine and push-doses of norepinephrine, have utility in the anesthesiology world, but we won’t discuss them for ED use here (see note below for why)*

Phenylephrine

Phenylephrine is a pure alpha-1 agonist that causes arterial vasoconstriction without a direct effect on heart rate. It’s most useful in situations where your patient is both hypotensive and tachycardic, due to its potential for reflex bradycardia when the baroreceptors sense an increased systemic vascular resistance.

Its onset of action is about 1 minute (typical dose: 50-200 mcg per push), and you may re-dose every 2-5 minutes to effect, which can last for around 10-20 minutes. The most notable indications for phenylephrine include refractory atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular rate, as well as septic shock and neurogenic shock (both types of distributive shock). However, because there is also a lot of wiggle room for provider preference in pressor choice, phenylephrine can also be used in other situations, such as hemorrhagic shock, or cardiac arrest with ROSC, as per provider discretion & clinical presentation.

Epinephrine

On the other hand, epinephrine has both alpha as well as beta 1/2 effects, meaning that it will both vasoconstrict while also increasing heart rate, due to its intrinsic inotropic/chronotropic effects. It is most useful in patients who are hypotensive when an increase in heart rate is desired. Such is the case in your hypotensive patient when you want to help the heart give a little extra squeeze while concomitantly clamping down on the peripheral vasculature (which can be beneficial in many situations).

Epinephrine’s onset of action is also about 1 minute with re-dosing to effect every 2-5 minutes (typical dose: 5-20 mcg per push), however the effects are slightly shorter than phenylephrine, with a duration of about 5-10 minutes (versus 10-20 minutes for phenylephrine). The most notable indications for epinephrine are cardiogenic shock and anaphylactic shock, with very good utility in many other situations such as septic shock, neurogenic shock, hemorrhagic shock, and cardiac arrest with ROSC, among others (again based on provider preference & clinical presentation).

As a notable aside, in cardiogenic shock, push-doses of epinephrine are preferred over phenylephrine due to epinephrine’s benefits of improved inotropy & chronotropy when the cardiac function is compromised. Phenylephrine is not recommended in cardiogenic shock because it may decrease cardiac output in these patients due to its potential for reflex bradycardia.

Table 1: Push Dose Vasopressors Comparison Chart [1,2]

(Note: Don’t forget, due to the short duration of action of these push-dose pressors, you will most likely be initiating a pressor drip after these pushes are given if you anticipate any type of sustained hypotension. Basically, get your nurses to start setting up a vasopressor drip of your choice in the meantime as you are giving push doses of pressors).

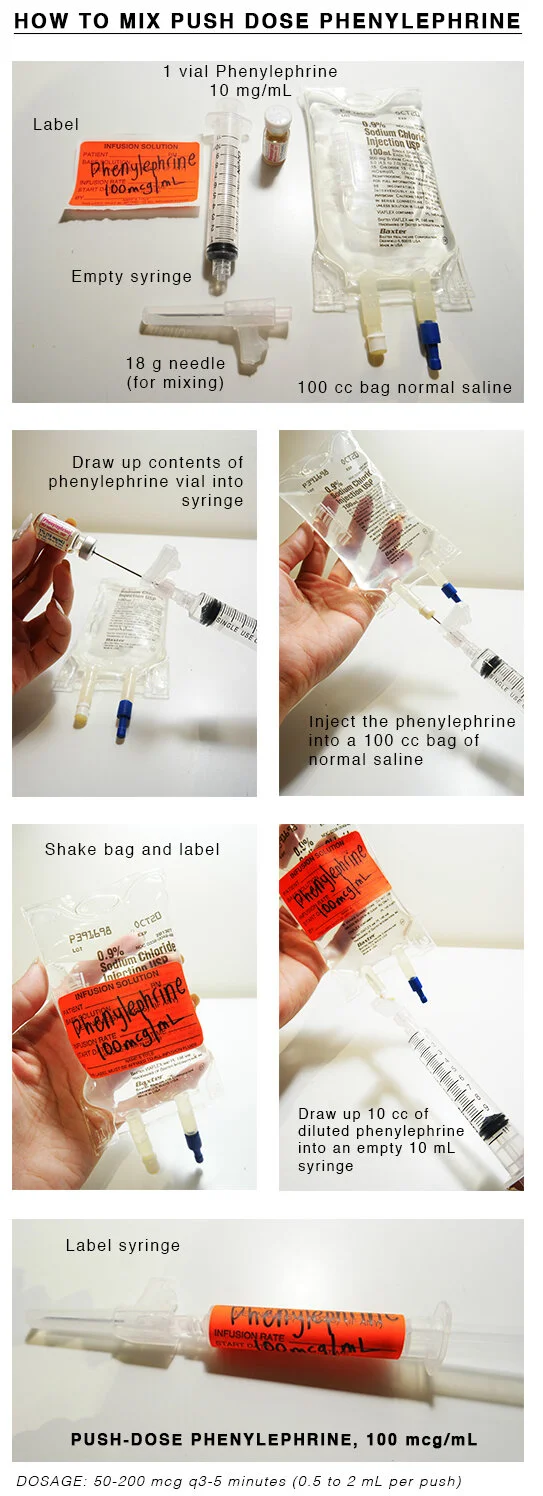

PUSH DOSE PRESSORS MIXING GUIDE

Push-dose epinephrine requires on-the-spot mixing due to its poor shelf stability (once mixed, push-dose epi should preferably be used within the hour and then tossed out), however some EDs may store pre-mixed, shelf-stable syringes of push-dose phenylephrine (“phenyl sticks” or “neo-sticks”) in their medication drawer. Nevertheless, you can very quickly & easily mix either of these two agents at patient’s bedside within seconds if you need it.

A WORD ON THE “DIRTY EPI DRIP”

For patients with severely low perfusion in which a formal drip is not immediately feasible and push-dose pressors would be insufficient (a common example being cardiac arrest), one last-ditch effort that some ED/ICU docs can employ in attempts to increase blood pressure, heart rate, & inotropy is the “dirty epi” drip, which is the street term for this drip, because you’re not going to find an order for it in your EMR, nor will you find it officially quoted in the literature anywhere (yet).

Its use is broadly not advised due to its imprecise dosing nature & inability to control the infusion, however, when time isn’t on your side and you need a pressor drip running on your patient ASAP while further measures are being employed, it’s an option you can throw out there as a last resort.

How to make it, you ask? Easy. Take an 1 mg (an amp) of crash cart epinephrine** and push the whole thing into a 1L bag of normal saline. Label it “Epinephrine 1mg/L” (never forget to label!), hang it, run it, and titrate it to effect.

Theoretically, 1 cc = 20 drops; therefore, ~2 drops per second = ~6 mcg/min [5]

Note, however, that your infusion rate will also be influenced by your needle gauge, patient positioning, gravity, etc., which is why the “dirty epi” drip is a very imprecise drip…you’ll never really know the true infusion rate.

As soon as possible, it is advisable to switch to a formal vasopressor drip such as norepinephrine to allow for more accurate control of pressor infusion rates.

CONCLUSION

To sum up, push-doses of vasopressors such as phenylephrine and epinephrine can come very handy in the ED when you know how to use them, and you can easily mix & administer them within seconds if your patient is severely hypotensive. Once you’re comfortable with the mixing process and dosing of each, you’ll have yourself a pocket-sized tool that can help you the next time you’re resuscitating a patient in shock and you need a quick fix.

BONUS: Quick tip!

Can’t remember which agent has the higher dose, longer duration, more steps in mixing, etc.? I like to remember that “PHENYL” is a longer word than “EPI,” therefore PHENYLEPHRINE has:

A higher target concentration in the final syringe (Phenylephrine 100 mcg/mL vs. Epinephrine 10 mcg/mL)

A higher dose-per-push than epinephrine (50-200 mcg phenylephrine vs. 5-20 mcg epinephrine).

More steps than epinephrine to dilute it to its final concentration (need to dilute phenylephrine into a 100cc bag NS first; see mixing guide above)

Longer duration than epinephrine (10-20 min for phenylephrine vs. 5-10 min for epinephrine)

*A word on other push-dose pressors such as ephedrine & norepinephrine: Anesthesiologists have frequently employed pushes of ephedrine in the OR for decades, however, due to its extended duration of action [60 minutes], its use is not recommended in the ED due to potential for over-correction of hypotension and adverse effects. There also has been some recent inquiry about the utility of push-dose norepinephrine in anesthesia literature, but evidence is limited on its use in the ED at this point, so we won’t discuss it here.

**Which epi for the “dirty epi” drip? Most people usually use 1 mg of crash cart epi for the dirty epi drip just because it’s the most readily available, but technically the more concentrated 1 mg of anaphylaxis epi would dilute to the same concentration in this situation.

References:

Moussavi, K. (2019). “Push-Dose Vasopressors: An Update for 2019.” [Web] EMdocs.net. Available at: http://www.emdocs.net/push-dose-vasopressors-an-update-for-2019/ [Accessed 10 Aug. 2019].

Weingart S. Push-dose pressors for immediate blood pressure control. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2015;2(2):131-132. doi:10.15441/ceem.15.010

Weingart, Scott. “EMCrit Podcast 6 – Push-Dose Pressors.” EMCrit Blog. Published on July 10, 2009. Available at https://emcrit.org/emcrit/bolus-dose-pressors/ [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

Weigand, Sabrina. The Use of Bolus-Dose Vasopressors in the Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine. 2018 March;50(3):72-76

Reuben (2009). “Dirty Epinephrine Drip.” [Web] Emergency Medicine Updates. Available at: https://emupdates.com/dirty-epi-drip/ [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

![Table 1: Push Dose Vasopressors Comparison Chart [1,2]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bc94f5b9b7d1515843688af/1579717750329-S5HPYPBPRYT21S3MHCZB/Screen+Shot+2019-10-14+at+8.19.25+PM.png)