Central Lines: Tips You Can't Miss

A collection of advanced central line considerations for intensivists.

Written by Dr Jeremy Riekena, Edited by Dr David Misch

Central venous catheter placement is among the core skills and procedures required in the field of emergency medicine and intensive care. Early learners are taught the basics of central line placement in the appropriate setting and gain proficiency throughout residency training, but as any experienced physician knows, proficiency does not equal expertise. As with any procedure, there is situational, positional, and anatomic variability that may lead to unexpected difficulties during central line placement. Thus, procedural mastery beyond the basics is essential for any practicing intensivist.

Choice of Invasive Lines:

Although central venous catheter placement is a standard skill of emergency medicine physicians and is versatile in many resuscitations, don’t forget that there are numerous other ways to obtain access that may be more appropriate than the standard triple lumen catheter.

Intraosseous Line:

IO lines are quick with multiple potential points of access. Patients who are intravascularly depleted may present with difficult IV access. In a crashing patient without adequate access, an IO line may be your best option. There’s a video showing the steps below:

Sheath Introducer:

This is the central catheter of choice in hypovolemic shock and most commonly used for volume resuscitation in massive hemorrhage. Conveniently, a triple lumen catheter can be placed through an introducer sheath (ex Cordis) if multiple central access points are needed during resuscitation. This is also a catheter that can accommodate a transvenous pacer when transitioning from transcutaneous pacing depending on your procedure kits available.

Hemodialysis Catheter:

Patients may present with such severe metabolic derangements or poisonings that they may need emergent dialysis via HD or CVVH. When placing these lines, be sure to have heparin flushed caps to maintain patency of these large central lines rather than standard central line caps flushed with saline.

RICC Line:

For patients with an established PIV and a vein moving proximally in a straight line, the PIV can be converted into a wide bore peripheral line. This is particularly helpful for rapid peripheral volume resuscitation that is even faster than a cordis. (1, 2)

Setting Up For Success

Positioning the patient in an appropriate manner to maximize your space and comfort of access will help your line go smoothly. When setting up, make sure to consider your own body position, hand dominance, tray placement, ultrasound position, as well as patient positioning.

Shoulder rolls:

Patients with stiff necks or redundant body tissue may be harder to position for access of the internal jugular vein. Simply placing a blanket or towel roll under the shoulder on the same side as the target vein shifts the patient’s head away from your site, giving a larger working field.

Trendelenburg:

For the internal jugular approach this position will help plump up your target vessel, which is especially helpful in volume depletion with small or easily collapsible veins. In the femoral approach, this can help mobilize redundant abdominal tissue and open up your site of access.

Side choice:

Practitioners will often place central lines on the patient side that matches the practitioner's own hand dominance, however, situations may arise where the opposite side needs to be accessed. This often happens due to anatomical considerations or saving a site for future procedures (cardiac cath, ECMO, dialysis catheter sites). When placing a line opposite of your preferred side, position the bed lower and slide the patient closer to you. This allows you to reach across their body to the insertion site to maintain a more comfortable and natural body position throughout the procedure.

Line Placement Skills and Problem Solving: Now that you’ve done 90% of the work setting up everything to optimize the line placement, it is still important to remember the small things during the procedure to prevent procedure failure. These are general skills that can be applied to all central line types and positions.

Confirmation of Location: Even under ultrasound guidance, artifacts and misalignment of the probe may give false reassurance that you are in the vessel lumen or the right vessel. Additionally, blood color is not always reliable to differentiate arterial vs venous blood in hypoxic states. It has been shown that inexperienced physicians have a high rate of posterior wall penetration and arterial system cannulation (3)

After placement of the guidewire, take advantage of the ultrasound already nearby to prove proper vessel placement from skin to central circulation. Ultrasound confirmation in 2 planes has been shown to have 100% sensitivity and specificity for confirmation of venous system placement. (4, 5)

(6)

Losing Blood Flow: This commonly occurs after successful aspiration of venous blood flow with a finder needle with subsequent loss of blood flow before threading the guidewire.

Needle stabilization is key to prevent this. When entering the skin, use controlled movement to avoid back wall puncture or vessel dissection.

Resting the entire medial aspect of your hand on the patient’s body after venous blood aspiration while removing the syringe prevents loss of needle position in the vessel lumen. Do not let your hand float in the air without sufficient anchoring.

Resistance with Guidewire Placement: There are times that you will still meet resistance while threading the guidewire even with smooth return of blood flow on initial aspiration.

If re-approaching the vessel, try to drop your finder needle angle to avoid backwalling or vessel dissection

You can try very slight back pressure against the guidewire, taking care to avoid kinking wire. This is done by advancing the guidewire and plastic housing ring as a single unit rather than threading the guidewire by itself. It is of absolute importance to only give slight pressure as it is still possible to dissect the vessel.

This is another great opportunity to utilize ultrasound to locate the tip of your finder needle and ensure it is in the center of your vessel as you attempt to advance your guidewire.

If that fails, attempt to retract and rotate the wire, then re-advancing the wire in an effort to move around mechanical obstructions with a great demonstration video below

Keeping a Clean Field: At this point, you will begin skin incision and dilation. Keeping a clean field is important in all lines for suturing and securing your line as well as avoiding misplacement of supplies. This is especially important in large lines such as a cordis and dialysis catheter.

Always have gauze nearby your working area and within quick reach. Placing gauze on the skin entry site while grabbing pieces for the next step of line placement is easy and keeps your field clean.

Preloading the skin dilator before scalpel incision allows for quick transition to skin dilation with less time for incised skin to bleed freely onto the field.

High Resistance with Dilation: As with every other step to this point, minimal exertion should be put forth to avoid distortion of anatomy and central line parts placed already.

Avoid skin bridges between the guidewire and incision site by cutting directly over the guidewire. Confirm the absence of a skin bridge by moving the wire with circumferential movements before dilation. Inability to move the wire in this fashion will reveal that the incision was not placed correctly over the path of the wire.

Larger incisions must be made with deeper vessels, usually occurring with femoral access. Keep in mind the depth of the vessel when visualizing with ultrasound to give guidance to how much space you have to incise and dilate.

Hold the dilator near the skin while advancing rather than at the back end of the dilator. This allows more direct pressure along the path of the wire and prevents wire kinking in subcutaneous tissue.

Follow path of wire created on initial approach with the finder needle. Do not create new angles with the dilator as this will kink your wire and make dilation extremely difficult.

Check that the wire moves freely within dilator lumen with subtle back and forth movements during dilation to confirm your correct path and angle. If the wire cannot move freely with small movements, retract the dilator until the wire is free and re-advance.

If dilation meets resistance after confirming free movement of the guidewire, the resistance is likely from skin and soft tissue. Small and quick twisting movements of the dilator to clear through subcutaneous tissue can be employed to continue adequate dilation. (7)

Depth of the Dilator:

To avoid vascular injury the dilator should only be advanced through the subcutaneous tissue to the vein wall (8). Pay attention to vein depth on ultrasound during guidewire placement and be mindful of increased depths with larger body habitus (9). Depth of the internal jugular vein is typically 1-2cm (10), is more superficial in the infraclavicular subclavian approach, and is closer to 2-3cm in the femoral vein approach (9)

Complications:

Employing the above techniques should lead to success in most circumstances, but we must always be prepared to handle worst case scenarios as intensivists.

Arterial Cannulation:

If an artery is cannulated: leave the catheter in, clamp and cap lines, and consult vascular surgery for endovascular and OR management. Similarly, if a guidewire is somehow left within the vessel, vascular surgery must be emergently consulted for operative management (11).

Tip Malposition:

Despite appropropriate approach and technique throughout central line placement, the tip of the central venous catheter may not end up appropriately in the super vena cava due to anatomic variants and body habitus. Chest x-ray after line placement will reveal if the tip is malpositioned.

Spontaneous correction may occur within one day without active re-correction. Although not standardly recommended, consider this option if central line use may be deferred. (12)

If the catheter is malpositioned outside of vasculature or misplaced in non-compressible sites, consult vascular surgery or interventional radiology for management recommendations.

Consider insertion of a new catheter after partial retrieval and redirection of the guide wire. (13-15)

If consult services are not available, it is reasonable to leave tips in the right atrium, superior vena cava, brachiocephalic vein, and subclavian vein as they have been shown to be safe with modern central line tips. (16)

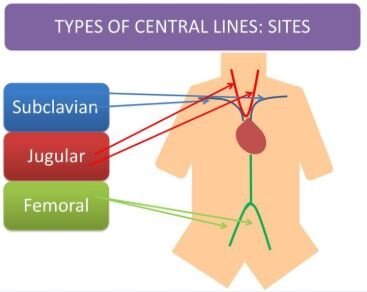

Site Choice for Central Venous Access: A Refresher

Complications to Consider

Infection: microbial colonization of catheter leading to blood stream infections

Thrombosis: catheter related thrombosis has potential for embolization

Mechanical: large pneumothorax, arterial injury, major bleeding

Internal Jugular

Advantage: Middle ground for thrombosis and mechanical complication rate requiring rescue intervention when compared to femoral and subclavian approach. It is also more approachable than the femoral approach when considering the need for patient repositioning.

Disadvantage: Highest infection rate in some studies, but often shows less infection than femoral approach.

Bottom Line: This is most often the most accessible and safest approach when balancing complication risk when all else is equal.

Femoral

Advantage: Lowest mechanical complication rate

Disadvantage: Thrombosis risk highest

Bottom Line: A good choice given that you can obtain dual cannulation of the femoral artery and vein in the same sterile field, saving time when managing a sick patient. (17)

Subclavian

Advantage: Lowest infection and thrombosis rate

Disadvantage: Highest mechanical complication risk

Bottom Line: There are times when the subclavian approach may be relatively safe or the only realistic option for central access. In trauma, patients are often in a C collar for cervical spine protection, making an internal jugular approach infeasible. When there is suspicion for abdominal or pelvic injury, a femoral line becomes unwise as there may be vessel compromise between the femoral vein and right atrium, making the subclavian approach the best of the three.

References

“How to Save a Life with a 20G IV.” Emergency Trauma Management, YouTube, 12 Feb. 2014, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AprH6bKEGtg&feature=emb_title.

Leeuwenburg, Tim. “How to Save a Life with a 20G IV – JAMIT Video.” ETM Course, 22 Mar. 2014, etmcourse.com/how-to-save-a-life-with-a-20g-iv-jamit-video/.

Blaivas, Michael, and Srikar Adhikari. “An Unseen Danger: Frequency of Posterior Vessel Wall Penetration by Needles during Attempts to Place Internal Jugular Vein Central Catheters Using Ultrasound Guidance.” Critical Care Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Aug. 2009, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19531950.

Stone, Michael B, et al. “Ultrasound Detection of Guidewire Position during Central Venous Catheterization.” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Jan. 2010, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20006207.

Scott Weingart. Podcast 156 – The Central Line Show – Part I: Avoiding Complications and Confirmation. EMCrit Blog. Published on August 29, 2015. Accessed on January 25th 2020. Available at [https://emcrit.org/emcrit/central-line-show/ ].

Pyeon, Taehee & Hwang, Jeong-Yeon & Gong, HyungYoun & Kwak, Sang-Hyun & Kim, Joungmin. (2018). Folded large-bore central catheter in the right internal jugular vein as shown by ultrasound: a case report. Journal of International Medical Research. 47. 030006051881351. 10.1177/0300060518813514.

Scott Weingart. EMCrit 254 – Central Line Tips and Tricks with Robby O and Me from EEM 2019. EMCrit Blog. Published on August 22, 2019. Accessed on January 25th 2020. Available at [https://emcrit.org/emcrit/emcrit-254-central-line-tips-and-tricks-with-robby-o-and-me-from-eem-2019/ ].

Robinson JF, Robinson WA, Cohn A, et al. Perforation of the great vessels during central venous line placement. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:1225.

De Sensi F, Miracapillo G, Addonisio L, et al. Predictors of Successful Ultrasound Guided Femoral Vein Cannulation in Electrophysiological Procedures. J Atr Fibrillation. 2018;11(3):2083. Published 2018 Oct 31. doi:10.4022/jafib.2083

American Association of Clinical Anatomists, Educational Affairs Committee. The clinical anatomy of several invasive procedures. Clin Anat. 1999;12:43–54.

Gibson, and Bodenham. “Misplaced Central Venous Catheters: Applied Anatomy and Practical Management.” OUP Academic, Oxford University Press, 5 Feb. 2013, academic.oup.com/bja/article/110/3/333/249469.

Rastogi, S, et al. “Spontaneous Correction of the Malpositioned Percutaneous Central Venous Line in Infants.” Pediatric Radiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Sept. 1998, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9732496/

Roldan, Carlos J, and Linda Paniagua. “Central Venous Catheter Intravascular Malpositioning: Causes, Prevention, Diagnosis, and Correction.” The western journal of emergency medicine vol. 16,5 (2015): 658-64. doi:10.5811/westjem.2015.7.26248

Gibson, F, and A Bodenham. “Misplaced Central Venous Catheters: Applied Anatomy and Practical Management.” British Journal of Anaesthesia, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Mar. 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23384735/.

Nayeemuddin, M, et al. “Imaging and Management of Complications of Central Venous Catheters.” Clinical Radiology, U.S. National Library of Medicine, May 2013, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23415017/.Farkas, Josh. “Does Central Line Position Matter? Can We Use Ultrasonography to Confirm Line Position?” EMCrit Project, 4 June 2017, emcrit.org/pulmcrit/does-central-line-position-matter-can-we-use-ultrasonography-to-confirm-line-position/.

Farkas, Josh. “Hemodynamic Access for the Crashing Patient: The Dirty Double.” EMCrit Project, 13 Dec. 2016, emcrit.org/pulmcrit/hemodynamic-access-for-the-crashing-patient-the-dirty-double/.

Parienti, Jean-Jacques, et al. “Intravascular Complications of Central Venous Catheterization by Insertion Site: NEJM.” New England Journal of Medicine, 14 Apr. 2016, www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1500964.