“It’s Probably Just Gas” Use of POCUS for Diagnosing Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Written by: Brian Smith, DO Edited by: Jeff Greco, MD

CASE:

You’re all alone on a particularly busy peds overnight shift and you see a 24-day-old male with the chief complaint of “abdominal swelling” pop up on your board. Per chart review, you learn the patient was born via vaginal delivery at 30 weeks gestation and that he stayed in the NICU for 8 days due to very low birth weight.

You go to see the patient and talk to his father at bedside. Patient’s father states this abdominal swelling started yesterday, but he didn’t bring the patient in initially because he thought it was “probably just gas” (spoiler alert: technically, he wasn’t wrong). However, today the patient had worsening swelling and multiple episodes of bilious vomiting and hematochezia, which prompted the father to bring him to the Emergency Department.

Vitals: Temp: 102 F, HR:190 bpm, RR: 50, BP: 80/40, O2 Saturation: 96% on RA, Weight: 1.5 kg

On physical exam, you see an ill-appearing, lethargic infant with sunken fontanelles, dry mucous membranes, and a markedly distended abdomen.

The team is having difficulty establishing venous access and an abdominal x-ray showed dilated bowel loops, but was otherwise unremarkable.

So now what do we do? Zofran, PO challenge, and discharge home?

Well considering it’s a Sono Sunday post, I think you can guess where this is headed…

USE OF POCUS FOR DIAGNOSING NECROTIZING ENTEROCOLITIS:

Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) is one of the most common gastrointestinal emergencies in the newborn infant. It is characterized by ischemic necrosis of intestinal mucosa with associated severe inflammation, invasion of enteric gas forming bacteria, and dissection of gas into the bowel wall and portal venous system.

The severity of NEC is classified by the Modified Bell staging Criteria (Figure 1). The incidence of proven or severe NEC (Bell stage II and III) is estimated to be 1-3 per 1000 live births

>90% of NEC cases occur in very low birth weight infants (BW < 1500 g) born at <32 weeks gestation, with an incidence from 2 to 7.5% in preterm infants with gestational age < 32 weeks. Incidence of NEC decreases with increasing birth weight and gestational age

Presenting signs and symptoms of NEC include: abdominal distention, vomiting (typically bilious), diarrhea, hematochezia, absent bowel sounds, abdominal wall erythema and crepitus, and nonspecific systemic findings such as apnea, lethargy, fever, and hypotension.

NEC has a high mortality rate - 35% for patients who did require surgery vs 21% for those who did not - so early recognition and treatment are critical.

Figure 1: Modified Bell’s staging Criteria (Kim)

Currently, plain abdominal radiography is the imaging modality of choice for NEC. The presence of pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) or portal venous gas (PVG)- caused by production of intraluminal gas by invading bacteria- is considered diagnostic of NEC and warrants treatment with bowel rest and prolonged antibiotics. The presence of free air- which is a sign of bowel perforation- is an indication for surgery. Although highly specific for NEC (92-100%), the sensitivity for abdominal radiography is low to diagnose pneumatosis (44%), portal venous gas (13%), and free air (52%). Most often, plain x-rays are unremarkable or show nonspecific findings such as gaseous intestinal distention, air-fluid levels, or bowel wall thickening.

There are many articles that advocate for the utility of POCUS as an adjunct to abdominal radiography, especially when abdominal radiography is nonspecific or unremarkable. Some of the justifications for the addition of POCUS in evaluation of NEC in infants include:

Ultrasound is readily available, noninvasive, and free from ionizing radiation.

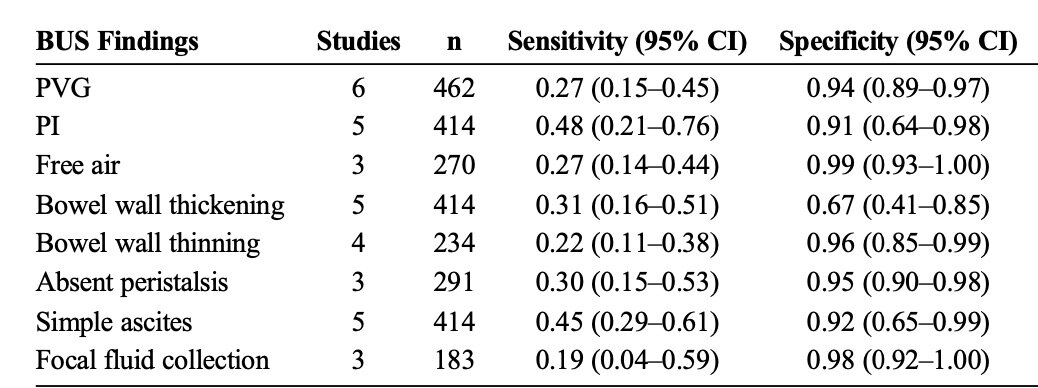

As demonstrated in a meta-analysis performed by Cuna et al, Bowel ultrasound has similar sensitivity and specificity for identifying classic signs of NEC compared to abdominal x-ray, and is possibly even more sensitive in identifying PI and PVG. (Figure 2) (Image 1)

POCUS also has the added benefits of giving more immediate insight into disease progression, as it can depict some features of NEC that cannot be seen with abdominal radiograph, such as bowel wall thickness and real-time evaluation of peristalsis and intestinal perfusion using color doppler. (Image 2)

Figure 2: Pooled Sensitivity and Specificity of Individual Bowel US Findings for Diagnosis of NEC in Neonates (Cuna et al 116)

Image 1: Examples of ultrasound findings in Necrotizing Enterocolitis, including (from left to right) Pneumatosis Intestinalis - hyperechoic reverberation artifact from air within the bowel wall, Portal Venous Gas - hyperechoic reverberation artifact from air along the venous system of the liver, Dilation of the intestinal loops with no visible peristalsis (Priyadarshi et al)

Image 2: Progression of NEC on Bowel US (Kim)

The sequence of color Doppler sonograms (bottom) demonstrating increasing severity of NEC is accompanied by simplified diagrams of a transverse section of bowel loop (top) demonstrating perfusion and bowel wall thickness. The timing of the progression from the phase of bowel wall thickening and hyperemia (B) to bowel wall thinning and absent perfusion (E) varies depending on the patient. However, it can be an incredibly rapid process.

Normal flow to normal bowl. The diagram shows normal bowel wall thickness and perfusion

The early changes of NEC are shown with bowel wall thickening (>2.5 mm) and hyperemia

The bowel wall thickening persists, but the perfusion has decreased

As the disease process becomes more severe, mucosa starts to slough and the bowel wall becomes much thinner (<1 mm), although there is still some perfusion.

The sloughing continues, the bowel wall becomes asymmetrically thinned, and blood flow ceases.

CONCLUSION:

While abdominal radiography is still the imaging modality of choice for diagnosing NEC, the use of POCUS as an adjunct diagnostic tool is becoming increasingly more popular. Although abdominal radiography and bowel ultrasound have similarly low sensitivities and high specificities for diagnosing NEC, bowel ultrasound can be incredibly useful in diagnosing NEC when abdominal x-ray findings are nonspecific or unremarkable. Additionally, unlikely abdominal radiography, bowel ultrasound can offer real-time insight into progression of disease. While sonographic findings of NEC are not currently included in the Bell Staging, future research should further probe the accuracy of POCUS as a whole in diagnosing NEC and consider integrating sonographic evidence of NEC into a comprehensive staging system. Doing so can be profoundly beneficial, as POCUS can help accurately and rapidly identify the progression of NEC, which can expedite appropriate management and potentially reduce the mortality rate.

Sources:

Cuna, Alain C., et al. “Bowel Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Necrotizing Enterocolitis.” Ultrasound Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 3, 2018, pp. 113–18. Pubmed, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29369246.

Kim, Jae. “Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis: Clinical Features and Diagnosis.” UpToDate, UpToDate, 18 June 2020, www.uptodate.com/contents/neonatal-necrotizing-enterocolitis-clinical-features-and-diagnosis.

Priyadarshi, Archana, et al. “Neonatologist Performed Point-of-Care Bowel Ultrasound: Is the Time Right?” Australasian Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine, vol. 22, no. 1, 2018, pp. 15–25. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ajum.12114, doi:10.1002/ajum.12114.

Raghuveer, Talkad S., et al. “Abdominal Ultrasound and Abdominal Radiograph to Diagnose Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Extremely Preterm Infants.” Kansas Journal of Medicine, vol. 12, no. 1, 2019, pp. 24–27. NCBI, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6396957.