The RAMER Reviews: Charcoal Chat

Written by: Joel Aguilar, MD; Edited by: Timothy Khowong, MD, MSEd

Background:

Let’s chat about charcoal. What is charcoal? Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue usually made from heating wood mixed with peat, coal, coconut shell or petroleum. The charcoal then becomes “Activated,” by a process that involves heating the substance at extremely high temperatures in the presence of a gas and, or another catalyst causing the charcoal to become porous and exponentially increases its surface area. One gram of activated charcoal has a surface area of approximately 3000m2. Dr. David Juurlink, Canadian toxicologist and pharmacologist, simplifies it best when he states that an average American football field has a surface area of a little over 4400m2. The adsorptive surface of activated charcoal contains several carbon moieties that adsorb different chemicals with varying affinity. These impressive properties are why AOC is referred to as “ black gold,” but why does this small, fine, black powder matter to us in the Emergency Room?

For decades now, as physicians we have been taught that activated oral charcoal can be used in the management of the acutely poisoned patient. It is believed that direct contact of activated charcoal within the gastrointestinal tract decreases the extent of absorption of the poison, thereby reducing or preventing systemic toxicity. The indications for oral activated charcoal have often been stated with ambiguity in medical literature, reporting that there are certain poisons that it may help treat and that it must be administered within 1 hour post poisoning. It is often rare that we see these cases, especially within that narrow time frame. So how did we formulate the current recommendations for administering OAC? In fact, there are no universal guidelines on when and how much to OAC to give. Like many toxicological interventions, we are inhibited from concrete human based evidence due to the ethical dilemmas that come with studying poisons. Some of our current guidelines on activated oral charcoal come from a position paper formed by the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology and European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists. The paper cites several In vitro, animal and volunteer studies to state that there may be benefit of AOC in the severely poisoned patient but the amount of the optimal dosing is unknown. They go on to declare that there are currently no sufficient clinical studies to assess the benefit of this intervention.

The Study:

Although the evidence isn’t concrete I would like to direct your attention to a small interesting study that demonstrates the effect of AOC. In 1982, a group of physicians at The University of Iowa performed a randomized crossover trial to demonstrate the effect of oral activated charcoal on the kinetics of IV theophylline. Theophylline, a methylxanthine, that comes in is an oral and IV form, acting as competitive nonselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor and nonselective adenosine receptor antagonist in order to relax smooth muscles and decrease inflammation commonly seen in patients with acute asthma or COPD exacerbation. This medication came into use during the 1930s and then fell out of favor in the late 1900s due to its side effect profile and the birth of our staple in asthma treatment, Albuterol and Ipratropium. This medications was reported to cause insomnia, severe GI symptoms, cardiac dysrhythmias and seizures.

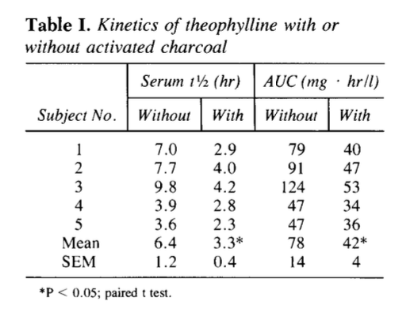

These physicians took 6 young, otherwise healthy, fasted male volunteers and administered a dose of 6 mg/kg IV theophylline with AOC at designated time intervals or water without AOC. Each volunteer underwent treatment on two separate occasions, separated by 5 days. They then measured the blood concentration of theophylline at multiple intervals throughout 24 hours. They found that the administration of repeated doses of AOC increased the total body clearance of theophylline. This study supports this idea of “Gut Dialysis.” At a certain point, our body reaches an equilibrium of metabolites of drugs or, in this case, toxins between the blood and the intestinal lumen. Gut dialysis describes this transfer of toxins from the blood to the intestines into the waste matter passing through our intestines and out of our systems. It is theorized that AOC works by binding specific poisons in the stomach. There are some poisons that may cause decreased gastric motility. In the severely poisoned patient, hypotension/hypoperfusion to the GI system may add to this delayed gastric emptying and further exposing the poison to the intralumen space to be diffused systemically. This would be an ideal situation for AOC in order to decrease the amount of poison being absorbed.

Conclusion:

With every intervention, there is always a concern for side effects. The biggest concern with AOC is the potential for aspiration. A patient’s mental status, ability to tolerate PO, and ability to tolerate multiple doses of this bitter tasting treatment must be taken into consideration before starting AOC. In the case that the patient cannot tolerate swallowing the AOC consider NGT tube placement or OGT to placement in your ventilated patient. Although the evidence isn’t strong and there are a handful of these small studies indicating some potential benefits, AOC is relatively safe treatment and under the right circumstances I would use this in my arsenal of treatments for the acutely poisoned patient. In summary…

Familiarize yourself with the current guidelines for AOC, where they come from and how strong they are.

Charcoal has some very interesting properties that make it an efficient treatment in decontamination

Consider your timeline of events, patients ability to cooperate with treatment, potential side effects, and type of poison before attempting AOC treatment.