Pelvic Fractures

Written by William Perkins, MD. Edited by Victor Huang, MD, CAQ-SM.

Case

A 45 year old man presents to the Emergency Department with severe suprapubic pain after being thrown off of a forklift at work. On examination, he is hemodynamically stable and the pelvis is stable, but there is significant pelvic tenderness to palpation, and blood at the urethral meatus.

What is the most likely diagnosis, typical mechanism of injury, expected physical exam findings, appropriate imaging modalities, and management plan?

Figure 1. AP view of the pelvis. Case courtesy of Dr. Andrew Dixon, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 31674.

Figure 2. Retrograde Urethrogram. Case courtesy of Dr. Andrew Dixon, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 31648.

Diagnosis: Bilateral pubic rami fractures with urethral injury on retrograde urethrogram.

Introduction

The bony pelvis is composed of 5 main elements: ilium, ischium, pubis, sacrum, coccyx. These are held together by strong ligaments. Fractures or ligamentous disruption indicate a high energy mechanism of injury. Mortality for pelvic fractures is around 10-13%, and if unstable, up to 50% [1].

Pelvic fractures can be broken down into three different types: acetabular fractures, single bone fractures, and pelvic ring fractures.

Single bone fractures are the most common type, particularly pubic rami fractures. Acetabular fractures are less common; the posterior wall is most likely to be injured. Pelvic ring fractures are the most severe and are often associated with vascular injury [2].

So let’s review our anatomy...

Anatomy of the Pelvis

Classification of Pelvic Fractures

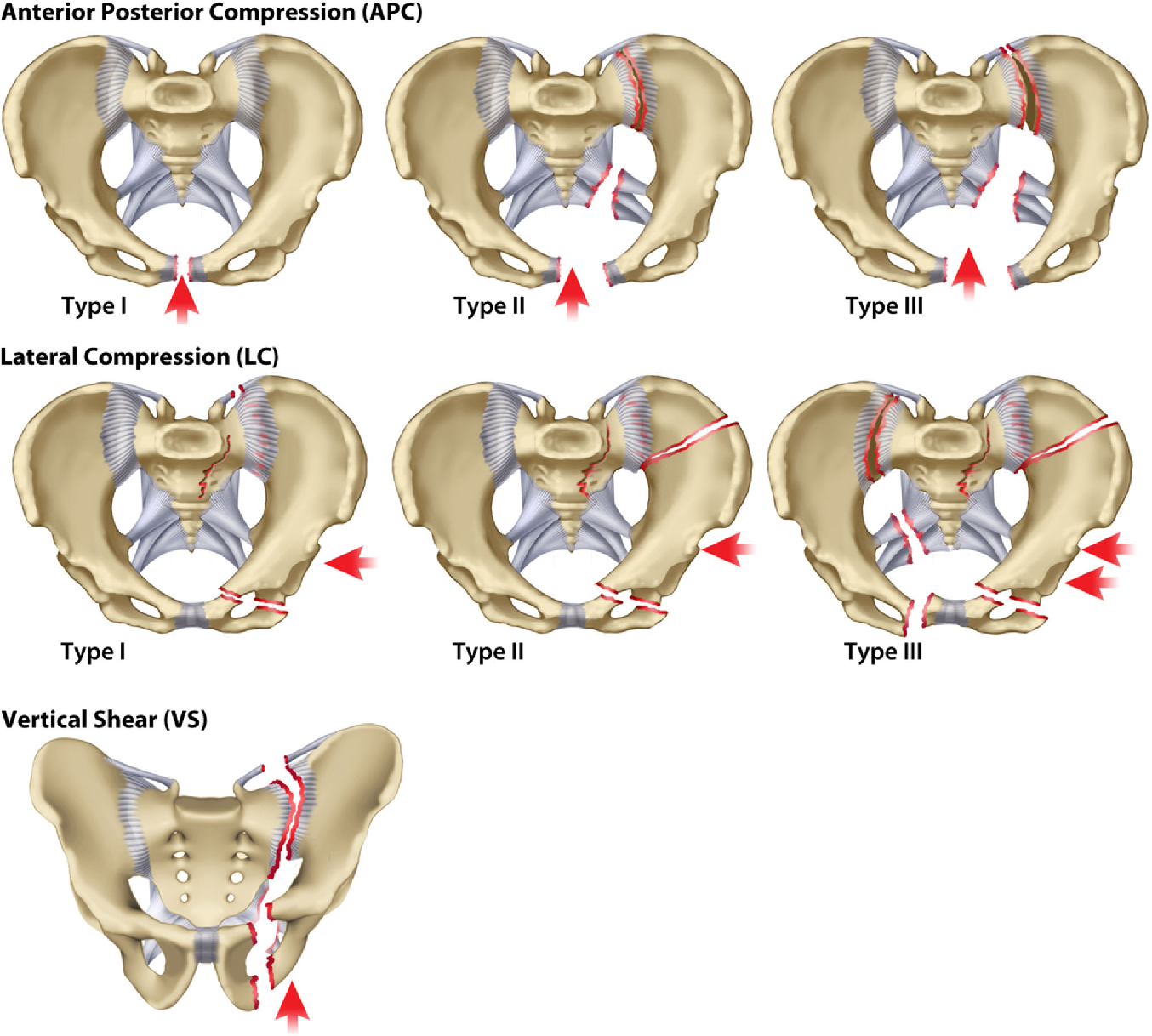

The Young-Burgess classification system differentiates types of pelvic fractures based on the primary mechanism as well as the extent of injury and instability. The three main patterns of injury by mechanism are Lateral Compression (LC), Anterior-Posterior Compression (APC), and Vertical Shear. LC and APC are further subdivided into 3 classes based on the severity of the injury [4].

Epidemiology and Mechanism of Injury

The incidence of pelvic ring fracture is approximately 23 per 100,000 persons. Pelvic fractures are seen in a bimodal distribution, with young men more likely to suffer from high energy trauma such as motor vehicle collisions and elderly females predisposed to osteoporosis more likely to suffer pelvic fractures after a low energy mechanism such as fall from standing [5].

The common mechanisms associated with pelvic ring fractures can be delineated by fracture pattern. AP and lateral compression fractures are commonly seen in roll-over MVCs or pedestrian-struck by motor vehicle. Vertical shear is more common with MVCs or falls from height where a significant force is transmitted upward through the lower extremities to the pelvis [6].

Physical Examination

Expect tenderness to palpation of the pelvis and hips. Evaluate for pelvic stability with manual compression to bilateral iliac crests. Examine the skin for ecchymosis around the lower abdomen and perineum. Pay close attention to the abdominal and GU exam to look for associated injuries. The rectal exam is important to check for tone and sensation in ruling out neurological injury. While the patient will likely have pain or difficulty moving one or both lower extremities, be sure to check each lower limb thoroughly to identify other possible associated fractures or neurovascular injuries [7].

Diagnostic Imaging

Plain film x-rays: in a critical trauma setting, you may only have time for the portable AP view. Other common views to isolate different parts of the bony pelvis include the inlet, outlet, and Judet views [8].

When reading a pelvic plain radiograph, look for any discontinuity in the “rings and lines” to assess for fractures. This includes the 3 pelvic rings, the iliopectineal, ilioischial, shenton and arcuate lines, as well as the anterior and posterior walls and the roof of the acetabulum.

As the pelvis is a complicated three dimensional structure, CT is often preferred over multiple xrays to better identify multiple fractures and to aid in operative planning. CT or CTA with contrast is also crucial for evaluation of associated injuries [7].

How to Read a Pelvic X-Ray

AP Radiograph of the Pelvis

Look for 3 Rings and Check for Discontinuity

Pelvic Ring

Obturator Foramen (Left)

Obturator Foramen (Right)

Pelvic Ring and Obturator Foramina

Check the Lines for Breaks

Iliopectineal Line: a break in this line indicates a fracture of the Anterior Column of the acetabulum

Ilioischial Line: indicates a fracture of the Posterior Column of the acetabulum

Teardrop (radiographic U): formed by the bony margins of the acetabular notch

Roof of the Acetabulum

Anterior Lip of the Acetabulum: often difficult to identify

Posterior Lip: seen laterally

Shenton Line - Curved line along the inferior border of the superior pubic ramus, and the inferomedial border of the femoral neck. When this line is disrupted, consider: femoral neck fracture or developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

Arcuate (Sacral Foraminal) Line: distortion of these lines raises concern for nondisplaced sacral ala fracture. Normally, they appear as symmetrical, fine, smooth, evenly curved cortical lines.

Retrograde Urethrogram Indications [10]

1. Blood at urethral meatus or gross hematuria

2. Difficulty/inability to void

3. “Butterfly pattern” of perineal bruising, scrotal or penile hematoma

4. High‐riding or freely mobile prostate on digital rectal exam

5. Displaced fractures of the pubic rami

6. Pelvic hematoma

Steps to Perform a RUG [11]

Obtain an xray scout film to ensure proper positioning

Place patient in 30 degrees lateral rotation

Pull the penis laterally to straighten the course of the urethra

This can be done manually while wearing a lead vest, or

Using a kerlix tied around the glans to distance oneself from the xray

Fill 50cc syringe with water soluble contrast (eg Cystografin)

Inject contrast (2 main options)

Foley - insert foley 2-3 cm into meatus and inflate balloon slightly, with 2-3 ml water, inject contrast using catheter tip

50cc luer lock syringe with the plastic catheter from a 14 gauge angiocath attached

Shoot xray every 10-20 cc of contrast injection to examine for extravasation.

Hold the glans tightly to prevent leakage of contrast out of the urethra

Contrast spilled on the bed will confound xray results.

Findings on a RUG

If no extravasation is identified on RUG, it is safe to attempt foley catheter placement.

Extravasation of contrast outside of the urethra is suggestive of urethral injury. Urology should be consulted. They will likely proceed with either careful foley placement or a suprapubic catheter.

Figure: Left: Retrograde Urethrogram without extravasation. Case courtesy of Dr. Matt A. Morgan, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 40478. Right: Retrograde Urethrogram with urethral disruption and contrast extravasation at the posterior urethra, but urethral injury is incomplete because contrast does ascend into the bladder. Case courtesy of Dr. Andrew Dixon, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 31648.

Management

Start with your ATLS. Remember that pelvic fractures are indicative of a high energy mechanism and you should systematically check for other injuries.

A pelvic binder should be considered for hypotensive pelvic fractures, particularly the “open book” AP-type. Lateral compression fracture patterns have the potential to be exaggerated with worsened injury if a pelvic binder is placed too tightly [Ghaemmaghami]. Pelvic binders are placed at the level of the greater trochanters.

Definitive management of the pelvic injury depends upon the extent of the fractures as well as associated injuries. Many of these injuries will require admission to the trauma service in the SICU or a surgical step-down floor. Interventional Radiology should be consulted for blush seen on angiography as these injuries carry high mortality. Any urethral or bladder injury identified clinically, on RUG, or CT will require a urology consult [8].

Considering the bony pelvis, stable fractures may be treated non-operatively. APC I and LC I on the Young-Burgess Classification system may be treated with protected weight bearing and physical therapy. Unstable fracture patterns such as APC II/III, LC II/III, and Vertical Shear should be treated operatively. These typically require open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) or anterior/posterior stabilization with plates & screws [8].

References

Manson T, O'Toole RV, Whitney A, Duggan B, Sciadini M, Nascone J. Young-Burgess classification of pelvic ring fractures: does it predict mortality, transfusion requirements, and non-orthopaedic injuries? J Orthop Trauma. 2010 Oct;24(10):603-9. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181d3cb6b. PMID: 20871246.

Gänsslen A, Pohlemann T, Paul C, Lobenhoffer P, Tscherne H. Epidemiology of pelvic ring injuries. Injury. 1996;27 Suppl 1:S-A13-20. PMID: 8762338.

Balogh Z, King KL, Mackay P, et al. The epidemiology of pelvic ring fractures: a population-based study. J Trauma. 2007;63(5):1066-73; discussion 1072-3. doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e3181589fa4.

Cullinane DC, Schiller HJ, Zielinski MD, Bilaniuk JW, Collier BR, Como J, Holevar M, Sabater EA, Sems SA, Vassy WM, Wynne JL. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guidelines for hemorrhage in pelvic fracture--update and systematic review. J Trauma. 2011 Dec;71(6):1850-68. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31823dca9a. PMID: 22182895.

Wong JM, Bucknill A. Fractures of the pelvic ring. Injury. 2017 Apr;48(4):795-802. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2013.11.021. Epub 2013 Dec 2. PMID: 24360668.

Griffin DR, Starr AJ, Reinert CM, Jones AL, Whitlock S. Vertically unstable pelvic fractures fixed with percutaneous iliosacral screws: does posterior injury pattern predict fixation failure? J Orthop Trauma. 2006 Jan;20(1 Suppl):S30-6; discussion S36. PMID: 16385205.

Davis DD, Foris LA, Kane SM, et al. Pelvic Fracture. [Updated 2021 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430734/

Perry K, Mabrouk A, Chauvin BJ. Pelvic Ring Injuries. [Updated 2021 Aug 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544330/

Jones, J., Er, A. Pelvic radiograph (an approach). Reference article, Radiopaedia.org. (accessed on 10 Nov 2021) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-28680

Uehara DT, Eisner RF. Indications for retrograde cystourethrography in trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 1986 Mar;15(3):270-2. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(86)80563-7. PMID: 3511789.

Kong JP, Bultitude MF, Royce P, Gruen RL, Cato A, Corcoran NM. Lower urinary tract injuries following blunt trauma: a review of contemporary management. Rev Urol. 2011;13(3):119-30. PMID: 22114545; PMCID: PMC3222924.

Ghaemmaghami V, Sperry J, Gunst M, Friese R, Starr A, Frankel H, Gentilello LM, Shafi S. Effects of early use of external pelvic compression on transfusion requirements and mortality in pelvic fractures. Am J Surg. 2007 Dec;194(6):720-3; discussion 723. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.040. PMID: 18005760.