Ortho Case: Finger Injury

Author: Will Perkins, MD , Editor: Victor Huang, MD

Case: A 45 year-old male presents to the ED with right hand pain after an e-bike accident. The patient was riding his electric bike at a high speed, wearing a helmet, when a car pulled out in front of him and he swerved to avoid it, falling to the ground. He denies any other site of pain or injury. Vital signs are stable. Physical exam shows deformity and tenderness at the 5th proximal phalanx. Pain improved with ketorolac and imaging was obtained.

Figure 1. Plain radiography of right hand with AP and oblique views. Author’s own images.

What is the diagnosis and management in the Emergency Department?

See below for answers!

Case Resolution:

The radiographs of the right hand showed a displaced, angulated transverse fracture of the proximal diaphysis of the 5th proximal phalanx, with apex volar angulation and 2 mm of displacement (Figure 1).

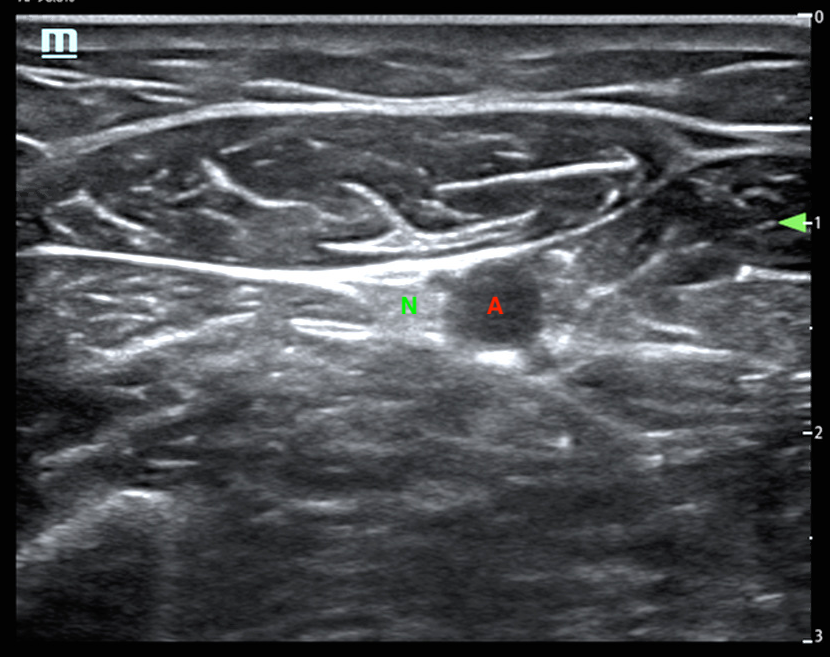

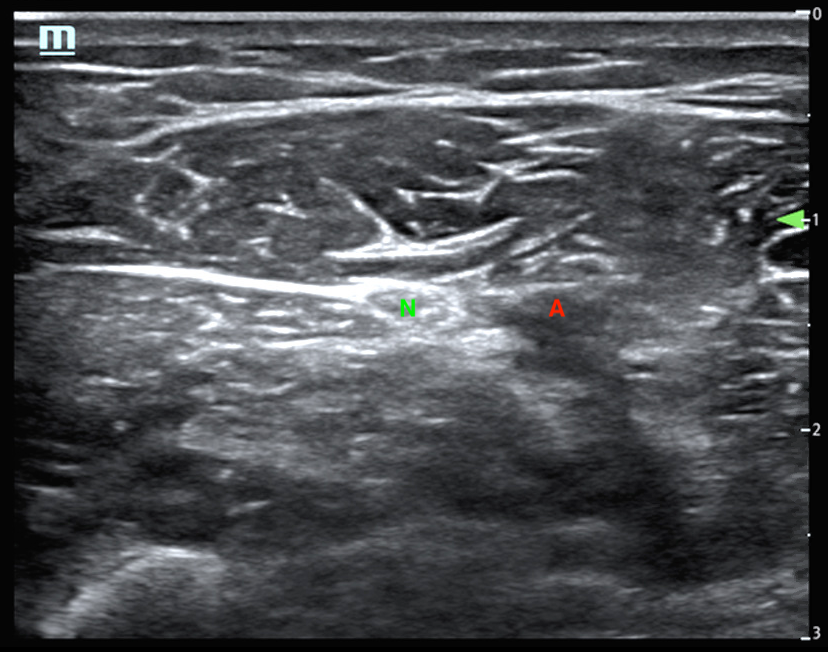

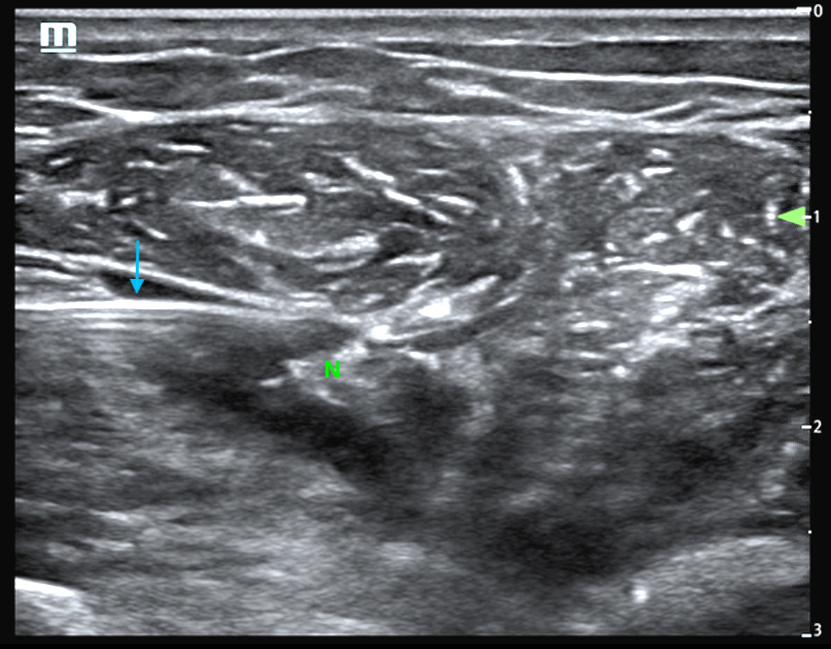

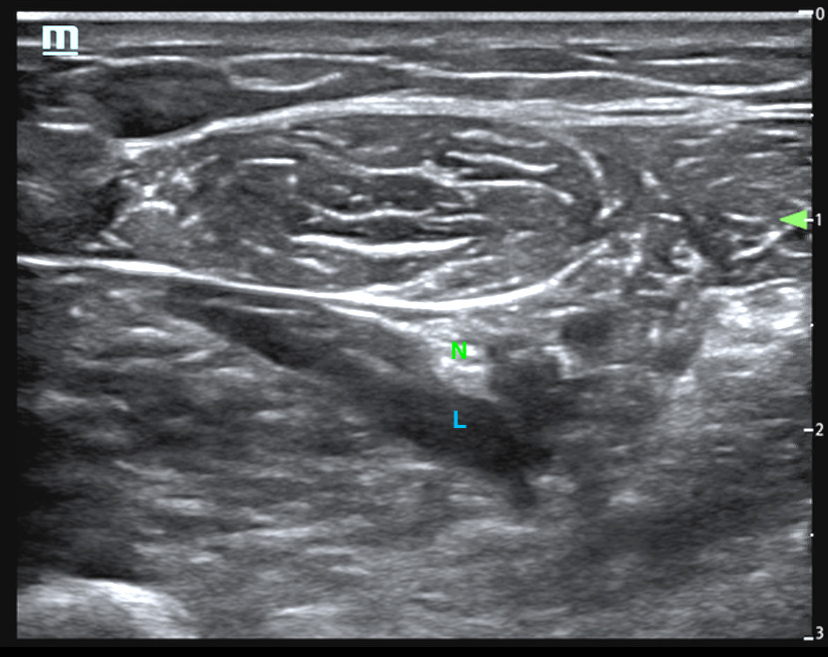

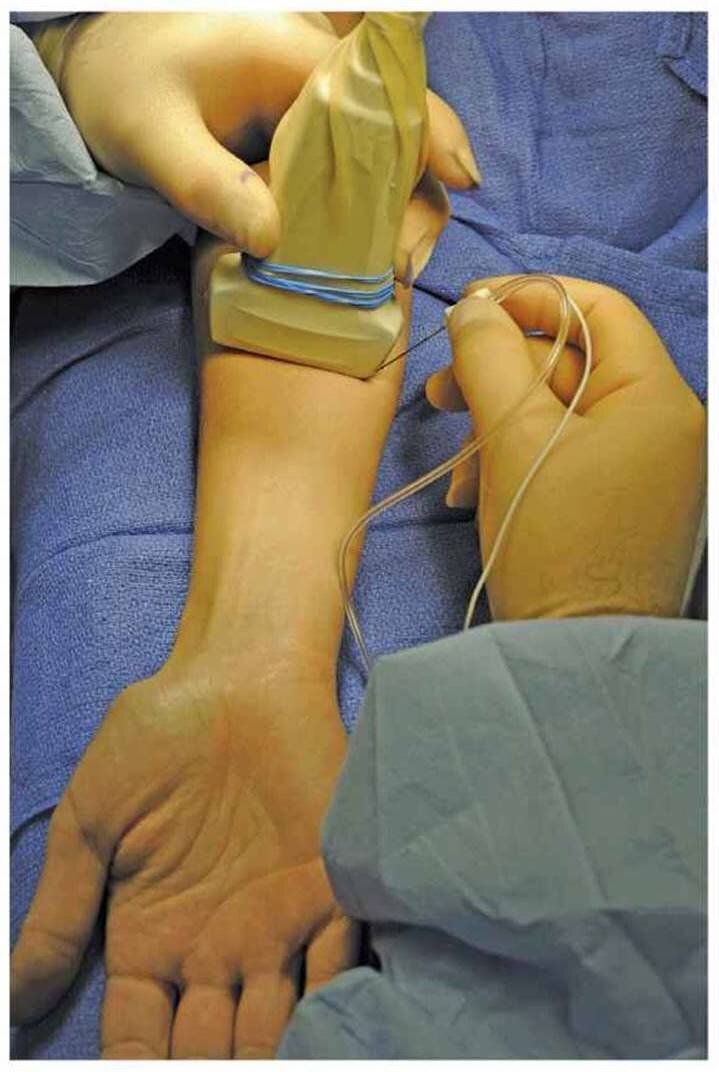

The patient was placed in a semi-fowler's position with the shoulder abducted and externally rotated, and elbow flexed to 90°. Ultrasound was used to identify the ulnar nerve at the medial volar aspect of the mid-forearm. The nerve was tracked proximally and distally to identify the preferred site for anesthetic infiltration, where the nerve was not immediately adjacent to the ulnar artery (Figure 2). The site was prepped with chlorhexidine and a small wheal of lidocaine injected. The needle was inserted several centimeters medially (in this position, away from the patient and towards the operator) in order to avoid the ulnar artery and with the goal of a true horizontal approach, parallel to the linear ultrasound footprint. The needle approach was monitored to avoid puncture of the nerve itself, overlying muscle, or laterally noted ulnar artery. The needle was advanced towards the nerve, and lidocaine injected in short bursts until the nerve was hydrodissected from surrounding fascia. Approximately 5 mL of 1% lidocaine was injected surrounding the ulnar nerve (Figure 3).

The patient reported numbness and decreased pain after 1-2 minutes. The proximal phalanx fracture was reduced and splinted in an ulnar gutter splint. He denied any pain or discomfort during the procedure. Post-reduction radiographs showed improvement in the fracture alignment (Figure 4). The patient was discharged with Orthopedic follow-up in one week.

Figure 2. Ultrasound images. A) The ulnar nerve (N) is seen in short-axis immediately adjacent to the ulnar artery (A) in the volar aspect of the mid-forearm. B) The nerve is followed proximally until the nerve (N) and artery (A) separate. Author’s own images.

Figure 3. Ultrasound images. A) The needle (arrow) is seen entering from the left side of the screen, in-plane to the ultrasound transducer. B) Infiltration of lidocaine (L) to bathe the ulnar nerve (N). Author’s own images.

Figure 4. Post-reduction films demonstrate reduction of the proximal phalanx fracture with improved alignment since prior exam. Author’s own images.

Discussion:

Phalanx fractures are very common and they account for 10% of all fractures and 1.5% of all ED visits [1,2]. The distal phalanx is most commonly fractured, followed by proximal, then middle [1,2].

Fractures occur most commonly due to sports or work-related injuries [1]. The mechanism of injury often dictates the type of fracture seen. A direct blow often causes a transverse or comminuted fracture, while twisting motions lead to an oblique or spiral fracture [1,3].

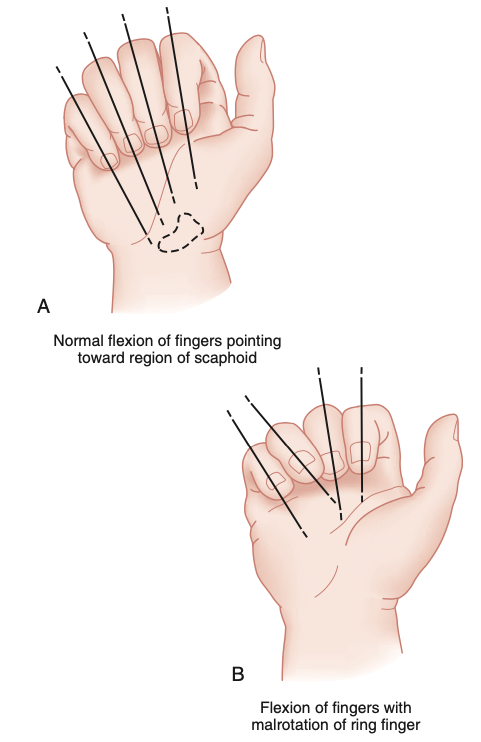

Physical examination should assess neurovascular status, tendon integrity and rotational alignment. Neurovascular exam includes two-point discrimination and capillary refill [1]. Tendon integrity is tested with flexion and extension of the MCP joint and of each IP joint. Assess rotational alignment by comparing the fingers to each other as well as the other hand (Figure 5A). When the fingers are flexed at the MCP and PIP, all four fingernails should be parallel and point towards the scaphoid or radial styloid [1,3,4]. Malrotation greater than 10 degrees can impair hand function and is an indication for surgery [1]. Assess skin integrity for lacerations or open wounds because open phalanx fractures are more common than metacarpal fractures [4].

Plain radiography should include AP, lateral and oblique views because angulation, shortening, and rotation may not be evident on a single view [1,2,4]. Rotational deformity can be seen on the lateral view if the diameters of the shaft at the fracture site do not appear equal [3]. CT imaging is rarely needed, but it may be helpful for operative planning for complex peri-articular fractures [2].

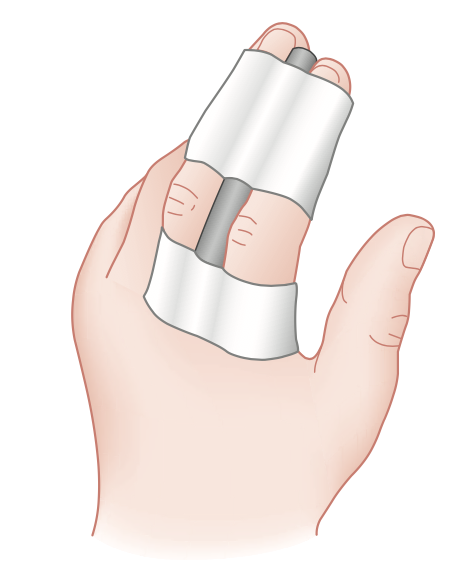

Stable, non-displaced transverse fractures can be managed with buddy-taping (Figure 6A) and early protected motion after pain and swelling subside to prevent joint stiffness [1,2,3,5]. These uncomplicated phalangeal fractures often heal well without complications. Outpatient follow-up is important to assess for development of angulation, malrotation, or translation, which can significantly impair fine motor skills and activities [1].

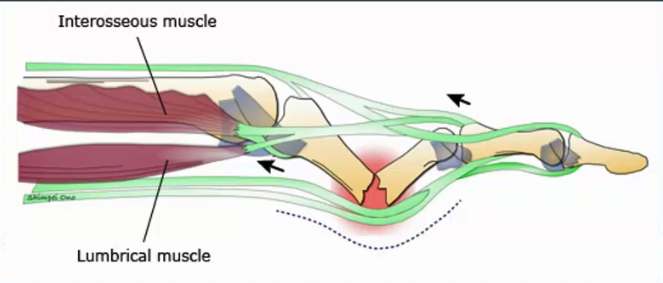

However, proximal phalanx fractures are often unstable with apex volar angulation and shortening due to the forces from the interosseous muscles and the extensors (Figure 5B) [1-3]. The interosseous muscles pull the proximal fracture fragment into flexion, while the extensor apparatus pulls the distal fragment into extension [1,5].

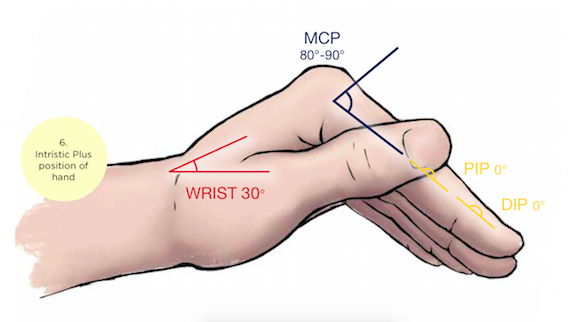

Unstable, oblique, angulated or displaced fractures require closed reduction and splinting in the ED after digital or regional nerve block [1,3]. The fracture should be immobilized in a gutter splint (ulnar or radial) in the “intrinsic-plus” position with 30° of wrist extension, 90° degrees of MCP flexion, and IP joints in extension (Figure 6 B and C) [1,2,5]. Imaging should be obtained after reduction to assess for stability [1].

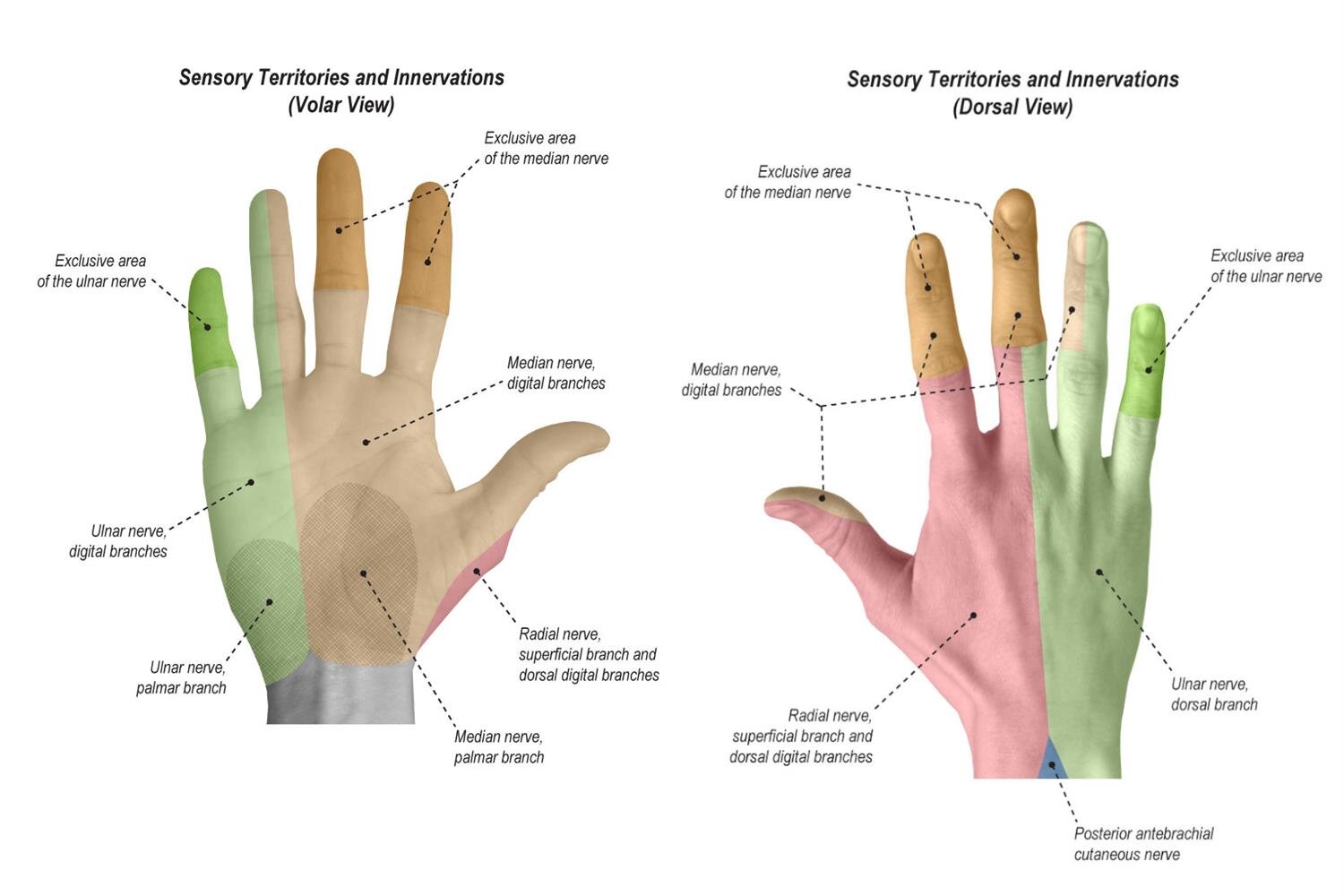

Peripheral nerve blocks may be preferred to digital blocks because the injection itself is less painful and it does not distort the tissue at the site of injury [6]. An ulnar nerve block can be utilized for analgesia during procedures or reductions occurring in the ulnar sensory distribution (Figure 7A) such as Boxer’s fracture, 5th phalangeal fractures, and medial hand lacerations [7]. Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve blocks (Figure 7B) have the added benefit of directly visualizing the neurovascular bundle to avoid intravascular injection as well as increasing the success of anesthesia [6].

Orthopedics referral is warranted for any proximal phalanx fracture that is not a closed, stable, transverse fracture with less than 2 mm displacement and less than 10° angulation and rotation [1,2,3,5]. Oblique, spiral, comminuted and intra-articular fractures are inherently unstable [3,5]. These usually require open reduction and internal fixation to obtain acceptable anatomic healing [1,3,4].

Figure 5. A) Examine fingers for malrotation. B) Interosseous muscles and extensor apparatus result in apex volar angulation of proximal phalanx fractures.

Figure 6. A) Buddy-tape for stable, non-displaced fractures. B) Ulnar gutter splint for displaced fractures. C) Intrinsic position is the optimal position of gutter splint immobilization.

Figure 7. A) Sensory distribution of peripheral nerves of the hand. B) Ultrasound-guided ulnar nerve block.

Figure 8. Stable, non-displaced 2nd proximal phalanx fracture. Unstable, displaced 3rd proximal phalanx fracture. Case courtesy of Andrew Murphy, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/41772">rID: 41772</a>

Figure 9. Salter-Harris type II proximal phalanx fracture. Case courtesy of Dr Bruno Di Muzio, <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/">Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href="https://radiopaedia.org/cases/38791">rID: 38791</a>

Figure: Displaced 4th proximal phalanx fracture with apex volar angulation. Author’s own images.

Works Cited:

Eiff MP, Hatch RL, Petering RC. Finger Fractures. Fracture Management for Primary Care. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2018: 36-62.

Kee C, Massey P. Phalanx Fracture. [Updated 2019 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545182/

Mailhot T, Lyn ET. Hand. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine Concepts and Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014: 534-569.

Atkinson R. Hand. DeLee & Drez’s Orthopaedic Sports Medicine: Principles and Practice. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009: 1379-1403.

Lögters TT, Lee HH, Gehrmann S, Windolf J, Kaufmann RA. Proximal Phalanx Fracture Management. Hand (N Y). 2018;13(4):376–383. doi: 10.1177/1558944717735947

Amini R, Javedani PP, Amini A, Adhikari S. Ultrasound-Guided Forearm Nerve Blocks: A Novel Application for Pain Control in Adult Patients with Digit Injuries. Case Reports in Emergency Medicine. 2016;2016:2518596. doi: 10.1155/2016/2518596

Ünlüer EE, Karagöz A, Ünlüer S, Oyar O, Özgürbüz U. Ultrasound-guided Ulnar Nerve Block For Boxer Fractures. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016;34(8):1726-1727. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.06.045