Hip Fractures

Written by Ari Nutovits, MD

Edited by Victor Huang, MD, CAQ-SM

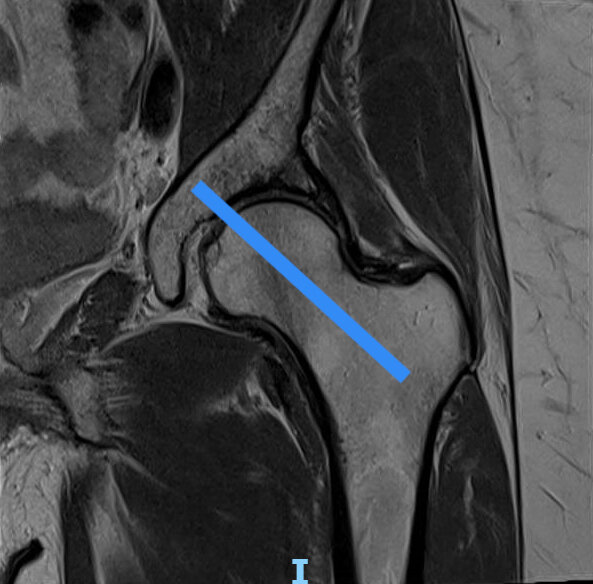

A 70-year-old male presents with left hip pain and inability to ambulate after a mechanical trip and fall. Examination demonstrates that the left lower extremity is shortened, abducted and externally rotated. Neurovascular examination is normal. Pain improved with acetaminophen and morphine and plain radiographs of the left hip are obtained. What is the most likely diagnosis and management plan?

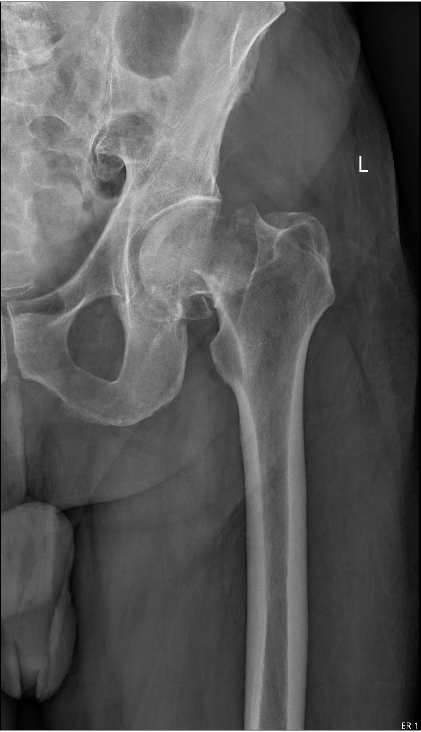

Figure 1. AP view of the pelvis and left hip demonstrating a displaced femoral neck fracture. Authors’ own images.

Introduction

Proximal femur, or hip fractures are a common injury with over 250,000 cases in the US each year [1]. They are associated with a high mortality rate with approximately one-third of patients dying within 1 year of the fracture [1-3]. Hip fractures are categorized into femoral neck, trochanteric, and subtrochanteric fractures [1].

The major risk factors for a hip fracture are age > 65, female sex, osteoporosis, lack of physical activity, dementia, cigarette smoking, increased fall risk, low socioeconomic status and family history or prior history of hip fracture [2,4]. The most common mechanism for a hip fracture is from a ground level fall on the affected hip [5].

Figure: Classification of hip fractures [2].

Clinical Evaluation

Physical examination may show the classic appearance of a shortened, abducted and externally rotated limb, but the deformity depends on the type of fracture and amount of displacement [3,4]. Pain is elicited with axial loading of the affected extremity or with the log roll maneuver, which involves gentle internal and external rotation of the lower leg in the supine position [4]. Patients should be examined for neurovascular compromise and any additional traumatic injuries [3].

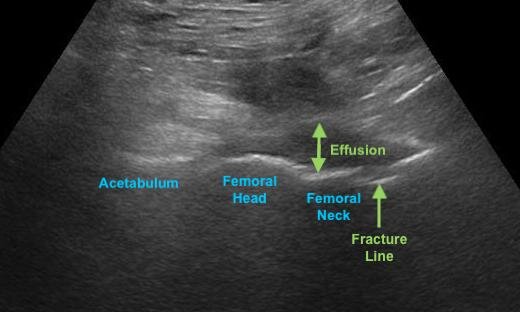

Plain radiography with AP of the pelvis and true lateral view of the hip should be performed [1,4]. Continued suspicion for a radiographically occult hip fracture warrants further imaging with a CT scan (sensitivity of 87%) or MRI (sensitivity of 100%) [6,7]. Ultrasound findings include joint effusion, hematoma and fracture line (see Figure 3) with a sensitivity of up to 100% [6].

Figure 3: Alignment of the ultrasound probe over the proximal femur and acetabulum (left). Ultrasound findings of hip fractures (right). Editor’s own image and illustration.

Management

It is important to provide multimodal pain control in the ED, which can include systemic analgesia and regional anesthesia. The fascia iliaca compartment block is a narcotic-sparing intervention that can be used for pre- and peri-operative pain control for hip fractures and reduces the incidence of delirium in elderly patients. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is a rare, but life-threatening complication that can be minimized with the use of ultrasound-guidance, aspiration, and dilution of the local anesthetic [8].

Figure 2: Ultrasound-guided fascia iliaca compartment block. Editor’s own image and illustration.

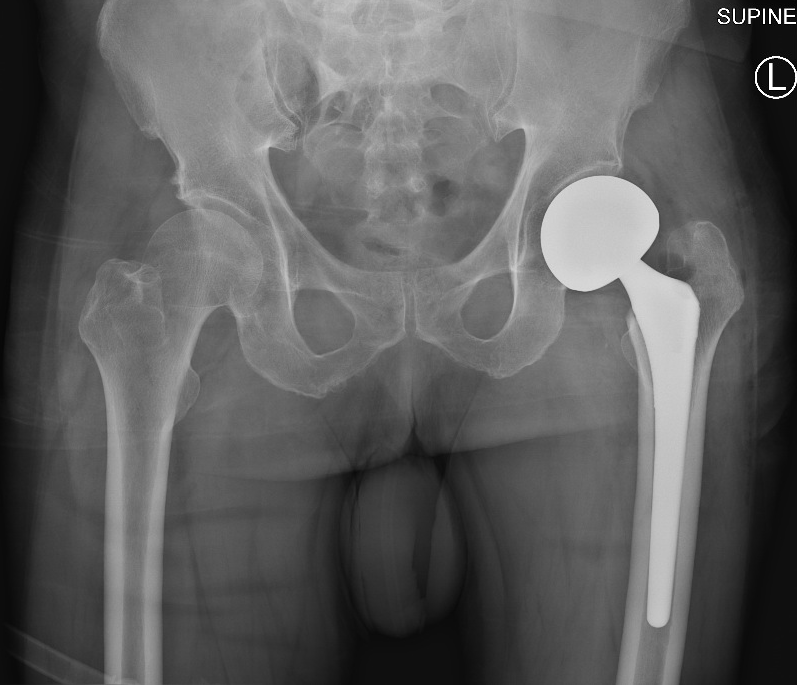

Hip fractures are categorized into femoral neck, trochanteric, and subtrochanteric fractures [1]. Intracapsular fractures like femoral neck fractures typically disrupt the blood supply to the femoral head and are associated with nonunion and avascular necrosis. Thus, hemi- or total hip arthroplasty is preferred over screw fixation in patients > 70 with displaced femoral neck fractures to minimize these complications [1,2].

Meanwhile, extracapsular fractures like intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures have an adequate blood supply and typically heal well after fixation with plates, sliding hip screws, or intramedullary nails [1,2].

Figure 4: Femoral neck fracture status post hemiarthroplasty. Authors’ own image.

References

Zuckerman JD. Hip Fracture. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(23):1519-1525. PMID: 8618608

Parker M, Johansen A. Hip fracture. Br Med J. 2006;333(7557):27-30. PMID: 16809710

Emmerson BR, Varacallo M, Inman D. Hip Fracture Overview. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Accessed December 10, 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32491446

LeBlanc KE, Muncie HL Jr, LeBlanc LL. Hip fracture: diagnosis, treatment, and secondary prevention. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(12):945-951. PMID: 25162161

Kelly DW, Kelly BD. A novel diagnostic sign of hip fracture mechanism in ground level falls: two case reports and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6(1):136. PMID: 22643013

Safran O, Goldman V, Applbaum Y, et al. Posttraumatic painful hip: sonography as a screening test for occult hip fractures. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28(11):1447-52. doi: 10.7863/jum.2009.28.11.1447. PMID: 19854958

Weber AE, Jacobson JA, Bedi A. A review of imaging modalities for the hip. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2013;6(3):226-234. PMID: 23784063

Steenberg J, Møller AM. Systematic review of the effects of fascia iliaca compartment block on hip fracture patients before operation. Br J Anaesth. 2018;120(6):1368-1380. PMID: 29793602

![Figure: Classification of hip fractures [2].](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5bc94f5b9b7d1515843688af/1609116276776-ZAFCPAFKIGDRZLECAO0R/Screen+Shot+2020-12-27+at+7.42.58+PM.png)