The Bridge to Norway

Written By: Tina Yang, DO; Edited by: Tim Khowong, MD

My third year of residency left me with new-found elective time; time to explore myself and expand my understanding of Emergency Medicine. In my junior year of college, I studied at the University of Oslo for a study abroad program. During that time, I came to admire the logistics of the Norwegian health care system. That led me to pursue my masters in International Health at Uppsala University in Sweden to advance my global health education. After starting residency, I knew I always wanted to pursue global health and I found another opportunity to go to Norway again. After reading the article by Dr. Galletta in ACEP Now discussing the establishment of emergency medicine as a new speciality in Norway, I knew I had to see for myself.

Like other Nordic countries, Norway has a free market economy with a well organized welfare system. It has one of the world's best healthcare systems, with universal health insurance and a strong primary care system that functions as a gatekeeper to other specialities. Patients who require inpatient treatment are referred to the hospital's akuttmottak or “acute receiving area” where patients would be processed for admission by an intern. The primary care physician (PCP) or legevakt, which means “doctor on call,” is required to refer patients to a specialty service at the hospital. Approximately 30% of patients arrive by ambulance, where out-of-hospital personnel determine the specialty service. Problems occur when patients are placed on to the service of the wrong specialist, for instance when back pain is referred to orthopedics although the cause is from an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Other issues develop when patients have multiple problems that span several specialties, such as a “patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with respiratory distress referred to surgery for a bowel obstruction; or when a patient has nonspecific symptoms such as dizziness.”1 The acute receiving areas are typically covered by nurses and resident physicians with an average of 6 months of clinical experience.

Since the emergency departments (EDs) in Norway were staffed with unsupervised interns, errors naturally occurred. A government report in 2008 performed an assessment of half of Norway's 54 acute receiving areas, which drew attention to unsupervised interns in the acute receiving areas and a failure in leadership. This has led to a significant change within the Norwegian medical society and the development of emergency medicine (EM) in Norway. From the establishment of the Norwegian Society for Emergency Medicine in 2010 to the creation of the specialty in 2017 and the approval of the first emergency physician in Norway in 2019, Norway has faced similar obstacles as the United States did with implementing the specialty 60 years ago.

Being a resident physician in the United States, we are fairly familiar with the healthcare system here. The United States has no single nationwide system of health insurance. Health insurance is purchased in the private marketplace or provided by the government to certain individuals. Private health insurance can be purchased from various for-profit commercial insurance companies or from non-profit insurers. The healthcare system in the US is flawed in many ways; compared to the US system, the European healthcare system has lower costs, more services, universal access to health care without financial barriers, and superior health status. Europeans have longer life expectancies and lower infant mortality rates than do US residents. I believe that there is much to learn from the established universal health care systems in Europe. I also believe that we have much to offer in terms of the medical evaluation and disposition of the undifferentiated patient, which became the basis of the cultural exchange I experienced in Norway.

Since finishing our rotation in Norway, we have learned much from their doctors and their system. In Norway, medical school starts immediately after high school. Medical school is a 6 year program. In their 5th year, medical students get a provisional license, which means they are overseen but can work as a licensed physician. They are only limited by the ability to prescribe certain medications or sick leave. Following their 6 years of medical school, all doctors must complete an 1-1.5 year internship, where they rotate to multiple specialities including internal medicine, general surgery, psychiatry, pediatrics, OBGYN and family medicine.

Our elective was through St. Olavs Hospital in Trondheim, which has the most developed EM program in Norway. Most other ERs in Norway do not have a dedicated EM residency program and are staffed primarily by internal medicine providers. The ER in Trondheim is staffed by EM residents as well as outside rotators from IM and other specialties such as general surgery and OMFS rotators. The residents don’t need to be overseen by an attending and they are responsible for their own patients. It’s their responsibility for poor outcomes if they don’t seek advice or help with management from their attendings. However since EM is such a novel part of medicine in Norway, residency is not tailored to them. There is minimal structure to their residency curriculum and they must fulfill requirements on their own. Additionally, most acute procedures done in the ER, such as central access and intubations and running codes, are usually performed by the attendings. During cardiac arrests, all the specialities are in the room - anesthesia for airway and central access, cardiology for the echo, EM physicians for running the code. Post resuscitation, they will all have a critical event debrief to talk about what went well during the code and how it can be improved. Furthermore, physicians in Norway also have the final say in a patient’s code status; if they deem that the resuscitation has a poor prognosis, the doctors can decide to terminate efforts, regardless of patient and family wishes.

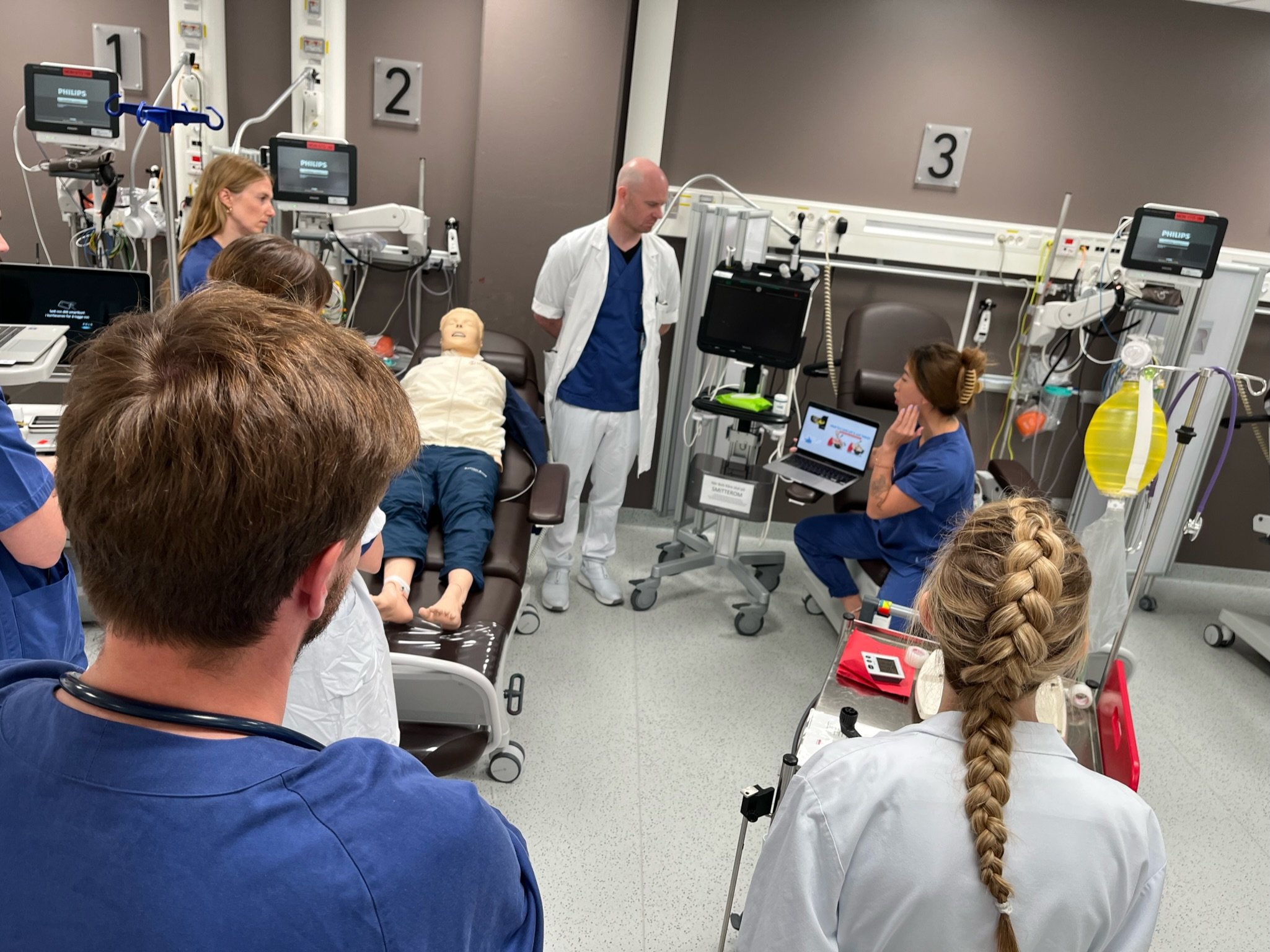

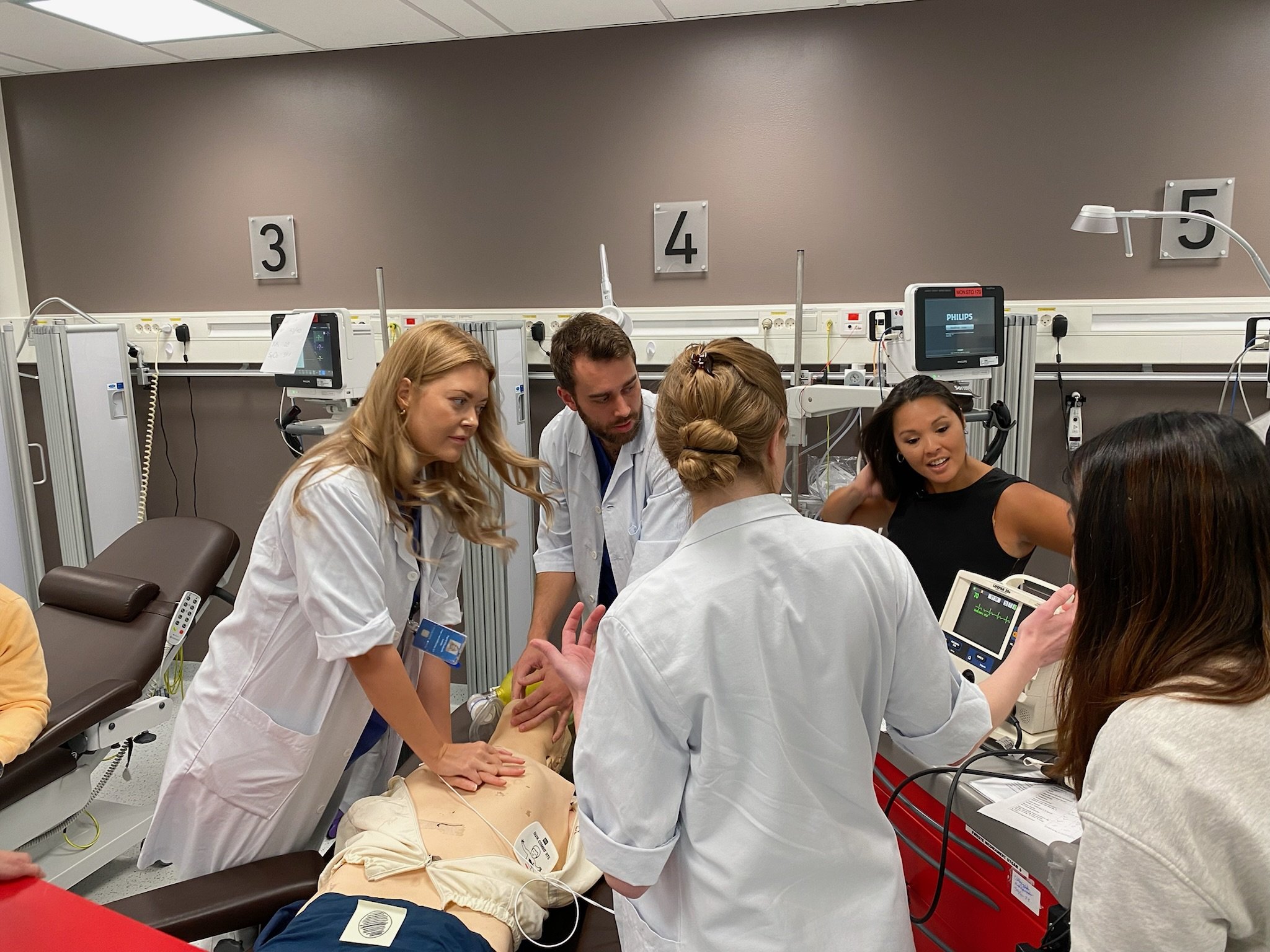

St. Olav’s Hospital (top left). Medical Simulation with some of our Norwegian Counterparts (bottom left). Our very own Dr. Nichlany and Dr. De Guzman enjoying traveling around St. Olav’s hospital on scooters (right).

We started our rotation in Norway by teaching ultrasound in their EDs and doing scan shifts. Patients are not allowed to come to the ER without prior referral by a PMD or from urgent care. If EMS is activated by the patient, the EMTs will come to the patient and can decide if the patient needs to be transported to an urgent care, to their primary care doctor’s office, to the ED or they can even cancel the activation. EMTs will usually consult the physician on call to make the decision or occasionally decide the course of treatment themselves. They will even get collateral and guidance from the patients’ primary care physician through phone call or an in-person visit, prior to going to the ER. In the ER, EM doctors have the power to change the patient’s acuity level.

Our team getting ready to teach ultrasound! From left to right we have Drs. Tina Yang, Anita Lui, Victor Bernal, Joel Aguilar, and Nate Zarider

Dr. Yang looking on enthusiastically as Dr. Lui teaches ultrasound to Norwegian physicians.

One of the most interesting aspects is that anesthesiologists in Norway have similar responsibilities to what we do as EM physicians in the USA. Anesthesia performs all the intubations whether it’s at the hospital or in the field. All the ICUs are run by anesthesiologists and they round with a multidisciplinary team every morning to decide care for that individual ICU patient. We had the exciting experience of doing a helicopter ride along with an anesthesiologist. We learned that the helicopter has ICU capabilities, including but not limited to ventilators, whole blood products, pumps, and a small ECMO machine. They also have REBOA on board! They have an active research trial across Norway that is looking at the use of ECMO in cardiac arrest and the possibility of better prognosis with its use.

During our time in Norway, we have learned so much through this international exchange. Their system is set up for continuity of care and for the use of specialists but is lacking our specialization in the assessment, stabilization, and disposition of the undifferentiated patient. While we had so much to teach them about that, they were able to teach us about the power of a system that is built to care for its patients over the pursuit of profit and how flexible other providers can be when practicing in a multitude of settings. Our hope for the future is to allow future NYPQ residents to participate in this global health elective in order to cultivate their knowledge in global health and medical education.

References

Galletta, G, Løvstakken, K. Emergency medicine in Norway: The road to specialty recognition. JACEP Open. 2020; 1: 790– 794. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12197